I am a geek, world history buff, my interests and hobbies are too numerous to mention. I'm a political junkie with a cynical view. I also love law & aviation!

Wednesday, August 26, 2020

Thursday, August 20, 2020

July 7, 2017) On March 1, 2017 Netherlands: Two New Laws and Decree on Right of Access to a Lawyer

Netherlands: Two New Laws and Decree on Right of Access to a Lawyer

(July 7, 2017) On March 1, 2017, two new laws and a decree, all related to the right of access to a lawyer before and during police questioning of a suspect, entered into force in the Netherlands. (Legislation Access Lawyer During Police Questioning in Force, Ministry of Security and Justice website (Feb. 27, 2017).)

A law adopted on November 17, 2016, transposes into Dutch law the corresponding European Union directive on the right of access to a lawyer. According to the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice, the new pieces of legislation balance the interests of the suspect and those of the investigation. (Id.; Act of 17 November 2016 Implementing Directive 2013/48/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 on the Right of Access to a Lawyer in Criminal Proceedings and in European Arrest Warrant Proceedings, and on the Right to Have a Third Party Informed upon Deprivation of Liberty and to Communicate with Third Persons and with Consular Authorities While Deprived of Liberty, STAATSBLAD VAN HET KONINKRIJK DER NEDERLANDEN [GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE KINGDOM OF THE NETHERLANDS, Stb.] 2016 Nr. 475 (Dec. 8, 2016, in force on Mar. 1, 2017), available at OVERHEID.NL (in Dutch); Directive 2013/48/EU…, 2013 OJ (L. 294) 1, EUR-LEX.)

The second law, also adopted on November 17, 2016, amends the Code of Criminal Procedure and some other legislation by adding new provisions on the accused, counsel, and some coercive measures. (Act of 17 November 2016, Amending the Code of Criminal Procedure and Some Other Laws Relating to the Addition of Provisions on the Accused, Counsel, and Some Coercive Measures, Stb. 2016 Nr. 476 (Dec. 8, 2016), available at OVERHEID.NL (in Dutch).) The law has supplementary measures pertaining to the initial phase of a criminal investigation, e.g., it extends the period of time that a suspect may be held for questioning from six hours to nine, to further enable access to legal counsel during questioning. (Legislation Access Lawyer During Police Questioning in Force, supra.)

Finally, the Decree of January 26, 2017, provides rules to implement the participation of counsel during investigative questioning. (Besluit van 26 januari 2017, houdende regels voor de inrichting van en de orde tijdens het politieverhoor waaraan de raadsman deelneemt (Besluit inrichting en orde politieverhoor), Stb. 2017 Nr. 29 (Feb. 9, 2017), available at OVERHEID.NL.) The legislation corresponds to a policy letter, applied by the Public Prosecution Service since March 1, 2016, that laid down rules of practice for the right to legal counsel prior to and during police questioning; it is also in line with EU regulations, decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, and case law of the Dutch Supreme Court. (Legislation Access Lawyer During Police Questioning in Force, supra.)

According to the Decree, counsel may make comments and ask questions “directly after the start and directly before the end of the questioning,” with the investigating officer in charge responsible for providing this opportunity to counsel. (Id.) During the questioning, lawyers are authorized to point out to the interrogating officer that, for example, the suspect did not understand the question asked or that the suspect’s physical or psychological state is impeding reliable continuation of the interrogation, and also to respond to the officer themselves if the suspect cannot freely make a statement, which constitutes, according to the Ministry of Security and Justice, a ban on coercive interrogations. (Id.)

The Decree also provides that the lawyer or the suspect him/herself “may ask for an interruption of the questioning, for mutual consultations” but the lawyer may “not answer any questions on behalf of the suspect, unless with the consent of the officer conducting the interrogation and of the suspect.” (Id.) The Decree indicates that the interrogating officer may, if he “considers it effective and reasonable,” permit the lawyer to play more of a role during questioning. (Id.) In addition, lawyers are to be given the opportunity to make remarks on how the questioning is represented when drawn up in the official report on the interrogation. (Id.)

Author: Wendy Zeldin

Topic: Criminal procedure, Detention

Jurisdiction: Netherlands

Date: July 7, 2017

Tuesday, August 11, 2020

Monday, July 20, 2020

Netherlands: Court Prohibits Government’s Use of AI Software to Detect Welfare Fraud (Mar. 13, 2020) On February 5, 2020

Netherlands: Court Prohibits Government’s Use of AI Software to Detect Welfare Fraud

(Mar. 13, 2020) On February 5, 2020, the District Court of The Hague (Rechtbank Den Haag) held that the System Risk Indication (SyRI) algorithm system, a legal instrument that the Dutch government uses to detect fraud in areas such as benefits, allowances, and taxes, violates article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (right to respect for private and family life).

Facts of the Case

The case was brought by several civil rights organizations, including the Netherlands Committee of Jurists for Human Rights (Nederlands Juristen Comité voor de Mensenrechten, NJCM), and two natural persons against the Dutch government. The Federation of Trade Unions in the Netherlands (Federatie Nederlandse Vakbeweging, FNV) intervened on behalf of the plaintiffs. The NJCM works to protect and strengthen fundamental human rights and freedoms. The FNV is a trade union that acts in the interests of its members and “is guided in part by the fundamental values of equality of all people, of freedom, justice and solidarity.” (District Court, paras. 2.2, 2.4 & 2.5.) The UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, submitted an amicus brief.

Decision

The Court first stated that social security is one of the pillars of Dutch society and contributes significantly to prosperity in the Netherlands. The fight against fraud, which is the stated aim of the SyRI legislation, is therefore crucial. It agreed with the government that new technologies such as the SyRI, which offer more possibilities to prevent and combat fraud, should be utilized and generally serve a legitimate purpose. However, the Court pointed out that the development of new technologies means that the right to respect for private life, which includes the right to the protection of personal data, is increasingly important and that the absence of sufficient and transparent protection of it might have a “chilling effect” among the population. (Paras. 6.3–6.5.)

The Court reiterated that the Netherlands has an obligation under article 8 of the ECHR to strike a fair balance between the interference with the right to respect for private life and the benefits of the use of new technologies to prevent and combat fraud. It held that the SyRI legislation fails to comply with that requirement because it is “insufficiently clear and verifiable.” It therefore declared article 65 of the SUWI Act and chapter 5a of the SUWI Decree incompatible with article 8, paragraph 2 of the ECHR. (Paras. 6.6 & 6.7.)

The Court focused its remarks on article 8 of the ECHR, but took the general principles of data protection codified in the EU Charter and the GDPR into account, because they offer the same level of protection. (Para. 6.41; EU Charter art. 52, para. 3.) According to the Court, it is undisputed that the SyRI legislation interferes with the right to respect for private life and that the Court must decide whether it is justified. The Court held that it cannot determine what exactly the SyRI is because the government has neither publicized the risk model and the indicators that make up the risk model nor submitted them to the Court. (District Court para. 6.49.) It ruled that the implementation of the SyRI legislation currently does not involve deep learning, data mining, and risk profile development but that it might in the future. (Para. 6.63.) Even though there is no random data collection, a large amount of data is collected, in the opinion of the Court. (Para. 6.50.) Finally, the Court stated that people whose data is collected and included in a risk report are not automatically informed. There is only a legal requirement to announce the start of a SyRI project. (Paras. 6.54 & 6.65.)

The Court reiterated the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights that states that any interference with the right to respect for private life must be provided for by law. It explained that it does not have to be a law in the formal sense, but that “some basis in domestic law” is sufficient. The legal basis must be sufficiently accessible and foreseeable, meaning it must be so clear that it is possible for an individual to adjust his or her behavior accordingly. In the case at issue, the Court left open the question whether the SyRI legislation is sufficiently accessible and foreseeable and concentrated on whether it was necessary in a democratic society. (Paras. 6.66–6.72.)

msdogfood@hotmail.com

(Mar. 13, 2020) On February 5, 2020, the District Court of The Hague (Rechtbank Den Haag) held that the System Risk Indication (SyRI) algorithm system, a legal instrument that the Dutch government uses to detect fraud in areas such as benefits, allowances, and taxes, violates article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (right to respect for private and family life).

Facts of the Case

The case was brought by several civil rights organizations, including the Netherlands Committee of Jurists for Human Rights (Nederlands Juristen Comité voor de Mensenrechten, NJCM), and two natural persons against the Dutch government. The Federation of Trade Unions in the Netherlands (Federatie Nederlandse Vakbeweging, FNV) intervened on behalf of the plaintiffs. The NJCM works to protect and strengthen fundamental human rights and freedoms. The FNV is a trade union that acts in the interests of its members and “is guided in part by the fundamental values of equality of all people, of freedom, justice and solidarity.” (District Court, paras. 2.2, 2.4 & 2.5.) The UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, submitted an amicus brief.

Decision

The Court first stated that social security is one of the pillars of Dutch society and contributes significantly to prosperity in the Netherlands. The fight against fraud, which is the stated aim of the SyRI legislation, is therefore crucial. It agreed with the government that new technologies such as the SyRI, which offer more possibilities to prevent and combat fraud, should be utilized and generally serve a legitimate purpose. However, the Court pointed out that the development of new technologies means that the right to respect for private life, which includes the right to the protection of personal data, is increasingly important and that the absence of sufficient and transparent protection of it might have a “chilling effect” among the population. (Paras. 6.3–6.5.)

The Court reiterated that the Netherlands has an obligation under article 8 of the ECHR to strike a fair balance between the interference with the right to respect for private life and the benefits of the use of new technologies to prevent and combat fraud. It held that the SyRI legislation fails to comply with that requirement because it is “insufficiently clear and verifiable.” It therefore declared article 65 of the SUWI Act and chapter 5a of the SUWI Decree incompatible with article 8, paragraph 2 of the ECHR. (Paras. 6.6 & 6.7.)

The Court focused its remarks on article 8 of the ECHR, but took the general principles of data protection codified in the EU Charter and the GDPR into account, because they offer the same level of protection. (Para. 6.41; EU Charter art. 52, para. 3.) According to the Court, it is undisputed that the SyRI legislation interferes with the right to respect for private life and that the Court must decide whether it is justified. The Court held that it cannot determine what exactly the SyRI is because the government has neither publicized the risk model and the indicators that make up the risk model nor submitted them to the Court. (District Court para. 6.49.) It ruled that the implementation of the SyRI legislation currently does not involve deep learning, data mining, and risk profile development but that it might in the future. (Para. 6.63.) Even though there is no random data collection, a large amount of data is collected, in the opinion of the Court. (Para. 6.50.) Finally, the Court stated that people whose data is collected and included in a risk report are not automatically informed. There is only a legal requirement to announce the start of a SyRI project. (Paras. 6.54 & 6.65.)

The Court reiterated the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights that states that any interference with the right to respect for private life must be provided for by law. It explained that it does not have to be a law in the formal sense, but that “some basis in domestic law” is sufficient. The legal basis must be sufficiently accessible and foreseeable, meaning it must be so clear that it is possible for an individual to adjust his or her behavior accordingly. In the case at issue, the Court left open the question whether the SyRI legislation is sufficiently accessible and foreseeable and concentrated on whether it was necessary in a democratic society. (Paras. 6.66–6.72.)

msdogfood@hotmail.com

Sunday, June 14, 2020

The Snowbirds, officially known as 431 Air Demonstration Squadron (French: 431e escadron de démonstration aérienne), are the military aerobatics or air show flight demonstration team of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Since the Snowbirds' first show in July 1971, there have been several incidents involving damage to airplanes, loss of airplanes, and loss of life. Below is a list of notable incidents only. There are other incidents, some involving loss of aircraft, that are not listed below.

DateLocationReasonCasualtiesDamage

10 June 1972 CFB Trenton, Ontario wingtip collision 1 fatality plane crashed

14 July 1973 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan bird strike caused engine stall back injuries plane crashed

16 July 1977 Paine Field, Washington collision during formation change none 2 planes crashed

3 May 1978 Grande Prairie, Alberta horizontal stabilizer failed 1 fatality plane crashed

17 June 1986 Carmichael, Saskatchewan mid-air collision minor injuries plane crashed

3 September 1989 Toronto, Ontario midair collision 1 fatality 2 planes crashed

26 February 1991 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan crashed during flight no serious injuries plane crashed

14 August 1992 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan failed engine bearing none plane crashed

22 October 1992 Bagotville, Quebec midair collision none 2 planes crashed

21 March 1994 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan engine failure minor injuries plane crash

24 September 1995 Point Mugu, California 3 planes collision with birds none planes damaged

7 June 1997 Glens Falls, New York touched wings none planes damaged

10 December 1998 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan mid-air collision 1 fatality plane crashed

27 February 1999 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan nose gear collapsed on landing none plane damage

4 September 2000 Toronto, Ontario planes touched none plane damage

10 April 2001 Comox, British Columbia nose & wing landing gear failed none plane damage

21 June 2001 near London, Ontario mid-air collision serious injuries [23] plane crashed

10 December 2004 Mossbank, Saskatchewan mid-air collision 1 fatality 2 planes crashed

24 August 2005 near Thunder Bay, Ontario engine failure minor injuries plane crashed

18 May 2007 near Great Falls, Montana restraining strap malfunction 1 fatality plane crashed

9 October 2008 near Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan pilot error 2 fatalities plane crashed

1 March 2011 Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan landed with gear up none plane damage

13 October 2019 Brooks, Georgia not yet known[24][25] minor injuries plane crashed

17 May 2020 Kamloops, British Columbia not yet known 1 fatality, 1 injured[26] plane crashed

FatalitiesEdit

Snowbird aircraft have been involved in several accidents, resulting in the deaths of seven pilots and two passengers and the loss of several aircraft. One pilot, Captain Wes Mackay, was killed in a automobile accident after a performance in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1988.[27] The RCAF commented: "... there is risk associated with formation flying. Flying by its very nature has an inherent element of risk. Eight Snowbird pilots have lost their lives in the performance of their duty. We remember them."[28]

10 June 1972: Solo Captain Lloyd Waterer died after a wingtip collision with the other solo aircraft while performing an opposing solo manoeuvre at the Trenton Air Show at CFB Trenton, Ontario.[29]

3 May 1978: Captain Gordon de Jong died at an air show in Grande Prairie, Alberta. The horizontal stabilizer failed, rendering the aircraft uncontrollable. Although pilot ejection was initiated, it was not successful.[30]

3 September 1989: Captain Shane Antaya died after a midair collision during a demonstration at the Canadian International Air Show during the CNE in Toronto, Ontario, when his Tutor crashed into Lake Ontario. During the same accident, team commander Major Dan Dempsey safely ejected from his aircraft.[31]

10 December 1998: Captain Michael VandenBos died in a midair collision during training near Moose Jaw.[32]

10 December 2004: Captain Miles Selby died in a midair collision during training near Mossbank, Saskatchewan, while practising the co-loop manoeuvre. The other pilot, Captain Chuck Mallett, was thrown from his destroyed aircraft while still strapped into his seat. While tumbling towards the ground, he was able to unstrap, deploy his parachute and land with only minor injuries.[33]

18 May 2007: Snowbird 2, Captain Shawn McCaughey fatally crashed during practice at Malmstrom Air Force Base near Great Falls, Montana, due to a restraining strap malfunction.[34]

9 October 2008: A Snowbird Tutor piloted by newly recruited team member Captain Bryan Mitchell with military photographer Sergeant Charles Senecal crashed, killing both, near the Snowbirds' home base of 15 Wing Moose Jaw while on a non-exhibition flight.[35][36]

17 May 2020: A Snowbird Tutor crashed in Kamloops, British Columbia, during a cross-country tour called "Operation Inspiration", intended to "salute Canadians doing their part to fight the spread of COVID-19."[37][38] Unit public affairs officer, Captain Jennifer Casey, died. The pilot, Captain Richard MacDougall, sustained serious injuries.[39][26]

Aircraft replacementEdit

Due to the age of the Tutors (developed in the 1950s, first flown in 1960, and accepted by the RCAF in 1963[40][41]), a 2003 Department of National Defence study recommended that the procurement process to replace the aircraft should begin immediately so the aircraft could be retired by 2010 because of obsolescence issues that would affect the aircraft’s viability.[42] Some concerns include outdated ejection seats and antiquated avionics.[43][44] There has also been criticism about the aircraft not being representative of a modern air force.[44] A 2008 review recommended that the Tutors' life could be extended to 2020 because of cost concerns related to purchasing new aircraft.[45] A 2015 report called "CT-114 Life Extension Beyond 2020", outlined planned upgrades to extend the life of the Tutor beyond 2020. These planned upgrades included replacing the ejection seats and wing components, and updating the brakes.[46] A further initiative to extend the life of the aircraft from 2020 to 2030 has been implemented by the RCAF. An April 2018 RCAF document mentioned that until a decision is made on replacement, the Snowbird Tutors will receive modernized avionics to comply with regulations. The new avionics will permit the team to continue flying in North America and allow the Tutors to fly until 2030. Upgrading work will begin in 2022.[45]

Notwithstanding any upgrades, the Government of Canada plans to replace the Tutors with new aircraft between 2026 and 2035, with a preliminary estimated cost of $500 million to $1.5 billion. Official sources were quoted: "The chosen platform must be configurable to the 431 (AD) Squadron standard, including a smoke system, luggage capability and a unique paint scheme. The platform must also be interchangeable with the training fleet to ensure the hard demands of show performances can be distributed throughout the aircraft fleet." [47] The objective of the Snowbird Aircraft Replacement Project is "to satisfy the operational requirement to provide the mandated Government of Canada aerobatic air demonstration capability to Canadian and North American audiences."[47]

ReferencesEdit

NotesEdit

^ Government of Canada, National Defence, Royal Canadian Air Force. "Members – Snowbirds – Demo Teams". www.rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

^ a b c Dempsey 2002, p. 567.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 718.

^ Canadian Armed Forces (29 July 2019). "CT-114 Tutor". www.rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

^ Canadian Armed Forces (13 October 2019). "CT1140071 Tutor - From the investigator". rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

^ Canadian Armed Forces (17 May 2020). "One Canadian Military Member Killed One Injured in CF Snowbirds Accident". rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 659.

^ "Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation." Archived 2009-08-23 at the Wayback Machine rafweb.org. Retrieved: 20 May 2011.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 95.

^ "Snowbirds – Full History." Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine RCAF. Retrieved: 15 March 2013.

^ "Snowbirds safety incident a factor behind air show cancellations". The Star, 18 May 2017 Retrieved: August 28, 2017

^ "FAQ: Snowbirds." Government of Canada, Royal Canadian Air Force, Retrieved: 4 September 2017

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 643.

^ "FAQ: Snowbirds." Government of Canada, Royal Canadian Air Force, 20 July 2015. Retrieved: 12 August 2015.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 540.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 538

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 545.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 552.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 597.

^ Dempsey 2002, pp. 605, 606.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 615.

^ Ewing-Weisz (2012).

^ [1] CBC News, 26 June 2001. Retrieved: 17 may 2020.

^ "Global News Story." Global News, 27 November 2019. Retrieved: 17 May 2020.

^ "Global News Story." Global News, 5 December 2019. Retrieved: 17 May 2020.

^ a b Ross, Andrea (16 May 2020). "Canadian Forces Snowbirds jet crashes in Kamloops, B.C., killing 1, injuring another". CBC News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

^ "Car Crash Kills Canadian Pilot, Injures Two Others" (Press release). AP News. 25 October 1988. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

^ "Snowbirds – Tributes." Royal Canadian Air Force, Government of Canada, 9 February 2015. Retrieved: 12 August 2015.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 546.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 569.

^ Dempsey 2002, p. 602.

^ "Snowbird crash, December 10, 1998 – investigation update." Archived June 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine airforce.forces.gc.ca, 7 June 2010. Retrieved: 16 June 2010.

^ "Canadian Forces Flight Safety Report: CT114173 / CT114064 Tutor". airforce.forces.gc.ca. 10 December 2004. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

^ "Canadian Forces Flight Safety Report: CT114159 Tutor." airforce.forces.gc.ca, 18 May 2007. Retrieved: 17 March 2014.

^ "CBC News Story." CBC, 10 October 2008. Retrieved: 13 October 2008.

^ "Canadian Forces Flight Safety Report." airforce.forces.gc.ca. Retrieved: 7 January 2017.

^ Kelly, Alanna (17 May 2020). "Snowbirds plane crashes near Kamloops, B.C." CTV News. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

^ "Canadian Forces Snowbirds launch cross-Canada tour" (Press release). Royal Canadian Air Force. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

^ Petruk, Tim (17 May 2020). "With video: Snowbird jet crashes into Kamloops house". Kamloops This Week. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

^ Canadair CT-114 Tutor Retrieved 29 May 2020

^ Milberry 1984, p. 346.

^ Replace Snowbird Jets ‘Immediately,’ DND Told in 2003. The Globe and Mail. April 25, 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2020

^ Snowbirds were waiting for new ejection seats before deadly crash. Now DND won’t say if gear was replaced. The Star. May 29, 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

^ a b Dempsey 2002, p. 694

^ a b Aircraft used by Snowbirds aerobatic team, on the go since 1963, will be kept flying until 2030. Saskatoon StarPhoenix. May 13, 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018

^ CT-114 Life Extension Beyond 2020 (archived). National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. Retrieved 30 May 2020

^ a b "Snowbird Aircraft Replacement Project." Government of Canada, 12 August 2015. Retrieved: 12 March 2015.

BibliographyEdit

Dempsey, Daniel V. A Tradition of Excellence: Canada's Airshow Team Heritage. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: High Flight Enterprises, 2002. ISBN 0-9687817-0-5.

Ewing-Weisz, Chris. "Lois Boyle was the ‘Mother of the Snowbirds’." The Globe and Mail, 17 January 2012, p. S8. Published online: 16 January 2012. Retrieved: 23 January 2012.

Fast, Beverley G. Snowbirds: Flying High, Canada's Snowbirds Celebrate 25 Years. Saskatoon, SK: Lapel Marketing & Associates Inc., 1995. ISBN 0969932707.

Milberry, Larry. Canada's Air Force At War And Peace, Volume 3. Toronto, ON: CANAV Books, 2000. ISBN 0-921022-12-3.

Milberry, Larry, ed. Sixty Years—The RCAF and CF Air Command 1924–1984. Toronto: Canav Books, 1984. ISBN 0-9690703-4-9.

Mummery, Robert. Snowbirds: Canada's Ambassadors of the Sky. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Reidmore Books, 1984. ISBN 0-919091-37-7.

Rycquart, Barbara. The Snowbirds Story. London, Ontario, Canada: Third Eye, 1987. ISBN 0-919581-41-2.

Sroka, Mike. Snowbirds: Behind The Scenes With Canada's Air Demonstration Team. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Fifth House Publishers, 2006. ISBN 1-894856-86-4.

External linksEdit

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snowbirds.

Canadian Forces Snowbirds (official site)

431 Squadron (Department of Defence – History and heritage)

Squadron history at Canadian Wings

Watch a 1980 NFB vignette on the Snowbirds

Thursday, May 7, 2020

Rosetta@home is a distributed computingproject for protein structure prediction on the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC) platform, run by the Baker laboratory at the University of Washington. Rosetta@home aims to predict protein–protein docking and design new proteins

Rosetta@home is a distributed computingproject for protein structure prediction on the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC) platform, run by the Baker laboratory at the University of Washington. Rosetta@home aims to predict protein–protein docking and design new proteins with the help of about fifty-five thousand active volunteered computers processing at over 494,953 GigaFLOPS on average as of March 26, 2020.[5] Foldit, a Rosetta@Home videogame, aims to reach these goals with a crowdsourcingapproach. Though much of the project is oriented toward basic research to improve the accuracy and robustness of proteomicsmethods, Rosetta@home also does applied research on malaria, Alzheimer's disease, and other pathologies.[6]

Like all BOINC projects, Rosetta@home uses idle computer processing resources from volunteers' computers to perform calculations on individual workunits. Completed results are sent to a central project server where they are validated and assimilated into project databases. The project is cross-platform, and runs on a wide variety of hardware configurations. Users can view the progress of their individual protein structure prediction on the Rosetta@home screensaver.

In addition to disease-related research, the Rosetta@home network serves as a testing framework for new methods in structural bioinformatics. Such methods are then used in other Rosetta-based applications, like RosettaDockor the Human Proteome Folding Project and the Microbiome Immunity Project, after being sufficiently developed and proven stable on Rosetta@home's large and diverse set of volunteer computers. Two especially important tests for the new methods developed in Rosetta@home are the Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) and Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions (CAPRI) experiments, biennial experiments which evaluate the state of the art in protein structure prediction and protein–protein docking prediction, respectively. Rosetta@home consistently ranks among the foremost docking predictors, and is one of the best tertiary structure predictors available.[7]

With an influx of new users looking to participate in the fight against the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, Rosetta@home has increased its computing power up to 1.7 PetaFlops as of March 28, 2020.[8][9]

Contents

1Computing platform

2Project significance

3Disease-related research

3.1Alzheimer's disease

3.2Anthrax

3.3Herpes simplex virus 1

3.4HIV

3.5Malaria

3.6Other diseases

4Development history and branches

4.1RosettaDesign

4.2RosettaDock

4.3Robetta

4.4Foldit

5Comparison to similar distributed computing projects

5.1Folding@home

5.2World Community Grid

5.3Predictor@home

6Volunteer contributions

7References

8External links

Computing platform[edit]

See also: List of distributed computing projects

The Rosetta@home application and the BOINC distributed computing platform are available for the operating systems Windows, Linux, and macOS; BOINC also runs on several others, e.g., FreeBSD.[10] Participation in Rosetta@home requires a central processing unit (CPU) with a clock speed of at least 500 MHz, 200 megabytes of free disk space, 512 megabytes of physical memory, and Internet connectivity.[11] As of July 20, 2016, the current version of the Rosetta Mini application is 3.73.[12] The current recommended BOINC program version is 7.6.22.[10] Standard Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) (port 80) is used for communication between the user's BOINC client and the Rosetta@home servers at the University of Washington; HTTPS (port 443) is used during password exchange. Remote and local control of the BOINC client use port 31416 and port 1043, which might need to be specifically unblocked if they are behind a firewall.[13] Workunits containing data on individual proteins are distributed from servers located in the Baker lab at the University of Washington to volunteers' computers, which then calculate a structure prediction for the assigned protein. To avoid duplicate structure predictions on a given protein, each workunit is initialized with a random seed number. This gives each prediction a unique trajectory of descent along the protein's energy landscape.[14] Protein structure predictions from Rosetta@home are approximations of a global minimum in a given protein's energy landscape. That global minimum represents the most energetically favorable conformation of the protein, i.e., its native state.

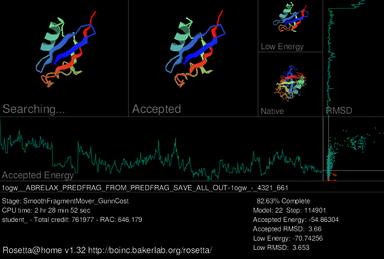

Rosetta@home screensaver, showing the progress of a structure prediction for a synthetic ubiquitin protein (PDB ID: 1ogw)

A primary feature of the Rosetta@home graphical user interface (GUI) is a screensaverwhich shows a current workunit's progress during the simulated protein foldingprocess. In the upper-left of the current screensaver, the target protein is shown adopting different shapes (conformations) in its search for the lowest energy structure. Depicted immediately to the right is the structure of the most recently accepted. On the upper right the lowest energy conformation of the current decoy is shown; below that is the true, or native, structure of the protein if it has already been determined. Three graphs are included in the screensaver. Near the middle, a graph for the accepted model's thermodynamic free energy is displayed, which fluctuates as the accepted model changes. A graph of the accepted model's root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), which measures how structurally similar the accepted model is to the native model, is shown far right. On the right of the accepted energy graph and below the RMSD graph, the results from these two functions are used to produce an energy vs. RMSD plot as the model is progressively refined.[15]

Like all BOINC projects, Rosetta@home runs in the background of the user's computer, using idle computer power, either at or before logging into an account on the host operating system. The program frees resources from the CPU as they are needed by other applications so that normal computer use is unaffected. Many program settings can be specified via user account preferences, including: the maximum percentage of CPU resources the program can use (to control power consumption or heat production from a computer running at sustained capacity), the times of day during which the program can run, and many more.

Rosetta, the software that runs on the Rosetta@home network, was rewritten in C++ to allow easier development than that allowed by its original version, which was written in Fortran. This new version is object-oriented, and was released on February 8, 2008.[12][16] Development of the Rosetta code is done by Rosetta Commons.[17] The software is freely licensed to the academic community and available to pharmaceutical companies for a fee.[17]

Project significance[edit]

Further information: Protein structure prediction, Protein docking, and Protein design

With the proliferation of genome sequencing projects, scientists can infer the amino acid sequence, or primary structure, of many proteins that carry out functions within the cell. To better understand a protein's function and aid in rational drug design, scientists need to know the protein's three-dimensional tertiary structure.

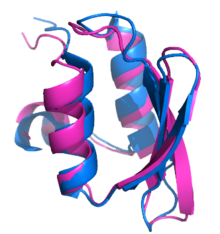

CASP6 target T0281, the first ab initio protein structure prediction to approach atomic-level resolution. Rosetta produced a model for T0281 (superpositioned in magenta) 1.5 Ångström (Å) RMSD from the crystal structure (blue).

Protein 3D structures are currently determined experimentally via X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The process is slow (it can take weeks or even months to figure out how to crystallize a protein for the first time) and costly (around US$100,000 per protein).[18] Unfortunately, the rate at which new sequences are discovered far exceeds the rate of structure determination – out of more than 7,400,000 protein sequences available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant (nr) protein database, fewer than 52,000 proteins' 3D structures have been solved and deposited in the Protein Data Bank, the main repository for structural information on proteins.[19] One of the main goals of Rosetta@home is to predict protein structures with the same accuracy as existing methods, but in a way that requires significantly less time and money. Rosetta@home also develops methods to determine the structure and docking of membrane proteins (e.g., G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs)),[20] which are exceptionally difficult to analyze with traditional techniques like X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, yet represent the majority of targets for modern drugs.

Progress in protein structure prediction is evaluated in the biannual Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiment, in which researchers from around the world attempt to derive a protein's structure from the protein's amino acid sequence. High scoring groups in this sometimes competitive experiment are considered the de facto standard-bearers for what is the state of the art in protein structure prediction. Rosetta, the program on which Rosetta@home is based, has been used since CASP5 in 2002. In the 2004 CASP6 experiment, Rosetta made history by being the first to produce a close to atomic-level resolution, ab initio protein structure prediction in its submitted model for CASP target T0281.[21] Ab initio modeling is considered an especially difficult category of protein structure prediction, as it does not use information from structural homology and must rely on information from sequence homology and modeling physical interactions within the protein. Rosetta@home has been used in CASP since 2006, where it was among the top predictors in every category of structure prediction in CASP7.[22][23][24] These high quality predictions were enabled by the computing power made available by Rosetta@home volunteers.[25] Increasing computing power allows Rosetta@home to sample more regions of conformation space (the possible shapes a protein can assume), which, according to Levinthal's paradox, is predicted to increase exponentially with protein length.

Rosetta@home is also used in protein–protein docking prediction, which determines the structure of multiple complexed proteins, or quaternary structure. This type of protein interaction affects many cellular functions, including antigen–antibody and enzyme–inhibitor binding and cellular import and export. Determining these interactions is critical for drug design. Rosetta is used in the Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions (CAPRI) experiment, which evaluates the state of the protein docking field similar to how CASP gauges progress in protein structure prediction. The computing power made available by Rosetta@home's project volunteers has been cited as a major factor in Rosetta's performance in CAPRI, where its docking predictions have been among the most accurate and complete.[26]

In early 2008, Rosetta was used to computationally design a protein with a function never before observed in nature.[27] This was inspired in part by the retraction of a high-profile paper from 2004 which originally described the computational design of a protein with improved enzymatic activity relative to its natural form.[28] The 2008 research paper from David Baker's group describing how the protein was made, which cited Rosetta@home for the computing resources it made available, represented an important proof of concept for this protein design method.[27] This type of protein design could have future applications in drug discovery, green chemistry, and bioremediation.[27]

Disease-related research[edit]

In addition to basic research in predicting protein structure, docking and design, Rosetta@home is also used in immediate disease-related research.[29] Numerous minor research projects are described in David Baker's Rosetta@home journal.[30] As of February 2014, information on recent publications and a short description of the work are being updated on the forum.[31] The forum thread is no longer used since 2016, and news on the research can be found on the general news section of the project.[32]

Alzheimer's disease[edit]

A component of the Rosetta software suite, RosettaDesign, was used to accurately predict which regions of amyloidogenic proteins were most likely to make amyloid-like fibrils.[33] By taking hexapeptides (six amino acid-long fragments) of a protein of interest and selecting the lowest energy match to a structure similar to that of a known fibril forming hexapeptide, RosettaDesign was able to identify peptides twice as likely to form fibrils as are random proteins.[34]Rosetta@home was used in the same study to predict structures for amyloid beta, a fibril-forming protein that has been postulated to cause Alzheimer's disease.[35] Preliminary but as yet unpublished results have been produced on Rosetta-designed proteins that may prevent fibrils from forming, although it is unknown whether it can prevent the disease.[36]

Anthrax[edit]

Another component of Rosetta, RosettaDock,[37][38][39] was used in conjunction with experimental methods to model interactions between three proteins—lethal factor (LF), edema factor (EF) and protective antigen (PA)—that make up anthrax toxin. The computer model accurately predicted docking between LF and PA, helping to establish which domains of the respective proteins are involved in the LF–PA complex. This insight was eventually used in research resulting in improved anthrax vaccines.[40][41]

Herpes simplex virus 1[edit]

RosettaDock was used to model docking between an antibody (immunoglobulin G) and a surface protein expressed by the cold sore virus, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) which serves to degrade the antiviral antibody. The protein complex predicted by RosettaDock closely agreed with the especially difficult-to-obtain experimental models, leading researchers to conclude that the docking method has potential to address some of the problems that X-ray crystallography has with modeling protein–protein interfaces.[42]

HIV[edit]

As part of research funded by a $19.4 million grant by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,[43]Rosetta@home has been used in designing multiple possible vaccines for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[44][45]

Malaria[edit]

In research involved with the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative,[46] Rosetta has been used to computationally design novel homing endonuclease proteins, which could eradicate Anopheles gambiae or otherwise render the mosquito unable to transmit malaria.[47] Being able to model and alter protein–DNA interactions specifically, like those of homing endonucleases, gives computational protein design methods like Rosetta an important role in gene therapy (which includes possible cancer treatments).[29][48]

Other diseases[edit]

Rosetta@home researchers have designed an IL-2 receptor agonist called Neoleukin-2/15 that does not interact with the alpha subunit of the receptor. Such immunity signal molecules are useful in cancer treatment. While the natural IL-2 suffers from toxicity due to an interaction with the alpha subunit, the designed protein is much safer, at least in animal models.[49] Rosetta molecular modeling suite was recently used to accurately predict the atomic-scale structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein weeks before it could be measured in the lab.[50]

Development history and branches[edit]

Originally introduced by the Baker laboratory in 1998 as an ab initio approach to structure prediction,[51] Rosetta has since branched into several development streams and distinct services. The Rosetta platform derives its name from the Rosetta Stone, as it attempts to decipher the structural "meaning" of proteins' amino acid sequences.[52] More than seven years after Rosetta's first appearance, the Rosetta@home project was released (i.e., announced as no longer beta) on October 6, 2005.[12] Many of the graduate students and other researchers involved in Rosetta's initial development have since moved to other universities and research institutions, and subsequently enhanced different parts of the Rosetta project.

RosettaDesign[edit]

Superposition of Rosetta-designed model (red) for Top7 onto its X-raycrystal structure (blue, PDB ID: 1QYS)

RosettaDesign, a computing approach to protein design based on Rosetta, began in 2000 with a study in redesigning the folding pathway of Protein G.[53] In 2002 RosettaDesign was used to design Top7, a 93-amino acid long α/β protein that had an overall fold never before recorded in nature. This new conformation was predicted by Rosetta to within 1.2 Å RMSD of the structure determined by X-ray crystallography, representing an unusually accurate structure prediction.[54] Rosetta and RosettaDesign earned widespread recognition by being the first to design and accurately predict the structure of a novel protein of such length, as reflected by the 2002 paper describing the dual approach prompting two positive letters in the journal Science,[55][56] and being cited by more than 240 other scientific articles.[57] The visible product of that research, Top7, was featured as the RCSB PDB's 'Molecule of the Month' in October 2006;[58] a superposition of the respective cores (residues 60–79) of its predicted and X-ray crystal structures are featured in the Rosetta@home logo.[21]

Brian Kuhlman, a former postdoctoral associate in David Baker's lab and now an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill,[59] offers RosettaDesign as an online service.[60]

RosettaDock[edit]

RosettaDock was added to the Rosetta software suite during the first CAPRI experiment in 2002 as the Baker laboratory's algorithm for protein–protein docking prediction.[61] In that experiment, RosettaDock made a high-accuracy prediction for the docking between streptococcal pyogenic exotoxin A and a T cell-receptor β-chain, and a medium accuracy prediction for a complex between porcine α-amylase and a camelid antibody. While the RosettaDock method only made two acceptably accurate predictions out of seven possible, this was enough to rank it seventh out of nineteen prediction methods in the first CAPRI assessment.[61]

Development of RosettaDock diverged into two branches for subsequent CAPRI rounds as Jeffrey Gray, who laid the groundwork for RosettaDock while at the University of Washington, continued working on the method in his new position at Johns Hopkins University. Members of the Baker laboratory further developed RosettaDock in Gray's absence. The two versions differed slightly in side-chain modeling, decoy selection and other areas.[39][62] Despite these differences, both the Baker and Gray methods performed well in the second CAPRI assessment, placing fifth and seventh respectively out of 30 predictor groups.[63] Jeffrey Gray's RosettaDock server is available as a free docking prediction service for non-commercial use.[64]

In October 2006, RosettaDock was integrated into Rosetta@home. The method used a fast, crude docking model phase using only the protein backbone. This was followed by a slow full-atom refinement phase in which the orientation of the two interacting proteins relative to each other, and side-chain interactions at the protein–protein interface, were simultaneously optimized to find the lowest energy conformation.[65] The vastly increased computing power afforded by the Rosetta@home network, combined with revised fold-tree representations for backbone flexibility and loop modeling, made RosettaDock sixth out of 63 prediction groups in the third CAPRI assessment.[7][26]

Robetta[edit]

The Robetta (Rosetta Beta) server is an automated protein structure prediction service offered by the Baker laboratory for non-commercial ab initio and comparative modeling.[66] It has participated as an automated prediction server in the biannual CASP experiments since CASP5 in 2002, performing among the best in the automated server prediction category.[67] Robetta has since competed in CASP6 and 7, where it did better than average among both automated server and human predictor groups.[24][68][69] It also participates in the CAMEO3D continuous evaluation.

In modeling protein structure as of CASP6, Robetta first searches for structural homologs using BLAST, PSI-BLAST, and 3D-Jury, then parses the target sequence into its individual domains, or independently folding units of proteins, by matching the sequence to structural families in the Pfam database. Domains with structural homologs then follow a "template-based model" (i.e., homology modeling) protocol. Here, the Baker laboratory's in-house alignment program, K*sync, produces a group of sequence homologs, and each of these is modeled by the Rosetta de novo method to produce a decoy (possible structure). The final structure prediction is selected by taking the lowest energy model as determined by a low-resolution Rosetta energy function. For domains that have no detected structural homologs, a de novo protocol is followed in which the lowest energy model from a set of generated decoys is selected as the final prediction. These domain predictions are then connected together to investigate inter-domain, tertiary-level interactions within the protein. Finally, side-chain contributions are modeled using a protocol for Monte Carlo conformational search.[70]

In CASP8, Robetta was augmented to use Rosetta's high resolution all-atom refinement method,[71]the absence of which was cited as the main cause for Robetta being less accurate than the Rosetta@home network in CASP7.[25] In CASP11, a way to predict the protein contact map by co-evolution of residues in related proteins called GREMLIN was added, allowing for more de novofold successes.[72]

Foldit[edit]

See also: Foldit

On May 9, 2008, after Rosetta@home users suggested an interactive version of the distributed computing program, the Baker lab publicly released Foldit, an online protein structure prediction game based on the Rosetta platform.[73] As of September 25, 2008, Foldit had over 59,000 registered users.[74] The game gives users a set of controls (for example, shake, wiggle, rebuild) to manipulate the backbone and amino acid side chains of the target protein into more energetically favorable conformations. Users can work on solutions individually as soloists or collectively as evolvers, accruing points under either category as they improve their structure predictions.[75]

Comparison to similar distributed computing projects[edit]

There are several distributed computed projects which have study areas similar to those of Rosetta@home, but differ in their research approach:

Folding@home[edit]

Of all the major distributed computing projects involved in protein research, Folding@home is the only one not using the BOINC platform.[76][77][78] Both Rosetta@home and Folding@home study protein misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, but Folding@home does so much more exclusively.[79][80] Folding@home almost exclusively uses all-atom molecular dynamics models to understand how and why proteins fold (or potentially misfold, and subsequently aggregate to cause diseases).[81][82] In other words, Folding@home's strength is modeling the process of protein folding, while Rosetta@home's strength is computing protein design and predicting protein structure and docking.

Some of Rosetta@home's results are used as the basis for some Folding@home projects. Rosetta provides the most likely structure, but it is not definite if that is the form the molecule takes or whether or not it is viable. Folding@home can then be used to verify Rosetta@home's results, and can provide added atomic-level information, and details of how the molecule changes shape.[82][83]

The two projects also differ significantly in their computing power and host diversity. Averaging about 6,650 teraFLOPS from a host base of central processing units (CPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs), and PS3s,[84] Folding@home has nearly 108 times more computing power than Rosetta@home.[85]

World Community Grid[edit]

Both Phase I and Phase II of the Human Proteome Folding Project (HPF), a subproject of World Community Grid, have used the Rosetta program to make structural and functional annotations of various genomes.[86][87] Although he now uses it to create databases for biologists, Richard Bonneau, head scientist of the Human Proteome Folding Project, was active in the original development of Rosetta at David Baker's laboratory while obtaining his PhD.[88] More information on the relationship between the HPF1, HPF2 and Rosetta@home can be found on Richard Bonneau's website.[89]

Predictor@home[edit]

Like Rosetta@home, Predictor@home specialized in protein structure prediction.[90] While Rosetta@home uses the Rosetta program for its structure prediction, Predictor@home used the dTASSER methodology.[91] In 2009, Predictor@home shut down.

Other protein related distributed computing projects on BOINC include QMC@home, Docking@home, POEM@home, SIMAP, and TANPAKU. RALPH@home, the Rosetta@home alpha project which tests new application versions, work units, and updates before they move on to Rosetta@home, runs on BOINC also.[92]

Volunteer contributions[edit]

Rosetta@home depends on computing power donated by individual project members for its research. As of March 28, 2020, about 53,000 users from 150 countries were active members of Rosetta@home, together contributing idle processor time from about 54,800 computers for a combined average performance of over 1.7 PetaFLOPS.[85][93]

Bar chart showing cumulative credit per day for Rosetta@home over a 60-day period, indicating its computing power during the CASP8 experiment

Users are granted BOINC credits as a measure of their contribution. The credit granted for each workunit is the number of decoys produced for that workunit multiplied by the average claimed credit for the decoys submitted by all computer hosts for that workunit. This custom system was designed to address significant differences between credit granted to users with the standard BOINC client and an optimized BOINC client, and credit differences between users running Rosetta@home on Windows and Linuxoperating systems.[94] The amount of credit granted per second of CPU work is lower for Rosetta@home than most other BOINC projects.[95]Rosetta@home is thirteenth out of over 40 BOINC projects in terms of total credit.[96]

Rosetta@home users who predict protein structures submitted for the CASP experiment are acknowledged in scientific publications regarding their results.[25] Users who predict the lowest energy structure for a given workunit are featured on the Rosetta@home homepage as Predictor of the Day, along with any team of which they are a member.[97] A User of the Day is chosen randomly each day to be on the homepage also, from among users who have made a Rosetta@home profile.[98]

References[edit]

^ "Rosetta@home License Agreement". Boinc.bakerlab.org. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

^ "Portfolio Highlight: Rosetta++ Software Suite". UW TechTransfer – Digital Ventures. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home".

^ "Rosetta@Home – Detailed stats | BOINCstats/BAM!".

^ "Rosette@home".

^ "What is Rosetta@home?". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Jump up to: a b Lensink MF, Méndez R, Wodak SJ (December 2007). "Docking and scoring protein complexes: CAPRI 3rd Edition". Proteins. 69 (4): 704–18. doi:10.1002/prot.21804. PMID 17918726.

^ "Rosetta@home - Server Status "TeraFLOPS estimate"". Rosetta@home. March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

^ "Rosetta@home Rallies a Legion of Computers Against the Coronavirus". HPCWire. March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

^ Jump up to: a b "Download BOINC client software". BOINC. University of California. 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home: Recommended System Requirements". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2008. Archived from the original on September 25, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Jump up to: a b c "Rosetta@home: News archive". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

^ "Rosetta@home: FAQ (work in progress) (message 10910)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2006. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Kim DE (2005). "Rosetta@home: Random Seed (message 3155)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home: Quick guide to Rosetta and its graphics". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2007. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Kim DE (2008). "Rosetta@home: Problems with minirosetta version 1.+ (Message 51199)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Jump up to: a b "Rosetta Commons". RosettaCommons.org. 2008. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Bourne PE, Helge W, eds. (2003). Structural Bioinformatics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-20199-1. OCLC 50199108.

^ "Yearly Growth of Protein Structures". RCSB Protein Data Bank. 2008. Retrieved November 30,2008.

^ Baker D (2008). "Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 55893)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Jump up to: a b "Rosetta@home: Research Overview". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2007. Archived from the original on September 25, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

^ Kopp J, Bordoli L, Battey JN, Kiefer F, Schwede T (2007). "Assessment of CASP7 predictions for template-based modeling targets". Proteins. 69 Suppl 8: 38–56. doi:10.1002/prot.21753. PMID 17894352.

^ Read RJ, Chavali G (2007). "Assessment of CASP7 predictions in the high accuracy template-based modeling category". Proteins. 69 Suppl 8: 27–37. doi:10.1002/prot.21662. PMID 17894351.

^ Jump up to: a b Jauch R, Yeo HC, Kolatkar PR, Clarke ND (2007). "Assessment of CASP7 structure predictions for template free targets". Proteins. 69 Suppl 8: 57–67. doi:10.1002/prot.21771. PMID 17894330.

^ Jump up to: a b c Das R, Qian B, Raman S, et al. (2007). "Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home". Proteins. 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

^ Jump up to: a b Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Andre I, et al. (December 2007). "RosettaDock in CAPRI rounds 6–12". Proteins. 69 (4): 758–63. doi:10.1002/prot.21684. PMID 17671979.

^ Jump up to: a b c Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, et al. (March 2008). "De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes". Science. 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

^ Hayden EC (February 13, 2008). "Protein prize up for grabs after retraction". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.569.

^ Jump up to: a b "Disease Related Research". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2008. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

^ Baker D (2008). "Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home Research Updates". Boinc.bakerlab.org. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

^ "News archive". Rosetta@home. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

^ Kuhlman B, Baker D (September 2000). "Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97(19): 10383–88. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710383K. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.19.10383. PMC 27033. PMID 10984534.

^ Thompson MJ, Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Ivanova MI, Baker D, Eisenberg D (March 2006). "The 3D profile method for identifying fibril-forming segments of proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (11): 4074–78. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.4074T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511295103. PMC 1449648. PMID 16537487.

^ Bradley P. "Rosetta@home forum: Amyloid fibril structure prediction". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Baker D. "Rosetta@home forum: Publications on R@H's Alzheimer's work? (message 54681)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Baker D (May 2005). "Improved side-chain modeling for protein–protein docking". Protein Science. 14 (5): 1328–39. doi:10.1110/ps.041222905. PMC 2253276. PMID 15802647.

^ Gray JJ, Moughon S, Wang C, et al. (August 2003). "Protein–protein docking with simultaneous optimization of rigid-body displacement and side-chain conformations". Journal of Molecular Biology. 331 (1): 281–99. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00670-3. PMID 12875852.

^ Jump up to: a b Schueler-Furman O, Wang C, Baker D (August 2005). "Progress in protein–protein docking: atomic resolution predictions in the CAPRI experiment using RosettaDock with an improved treatment of side-chain flexibility". Proteins. 60 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1002/prot.20556. PMID 15981249.

^ Lacy DB, Lin HC, Melnyk RA, et al. (November 2005). "A model of anthrax toxin lethal factor bound to protective antigen". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (45): 16409–14. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10216409L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508259102. PMC 1283467. PMID 16251269.

^ Albrecht MT, Li H, Williamson ED, et al. (November 2007). "Human monoclonal antibodies against anthrax lethal factor and protective antigen act independently to protect against Bacillus anthracis infection and enhance endogenous immunity to anthrax". Infection and Immunity. 75 (11): 5425–33. doi:10.1128/IAI.00261-07. PMC 2168292. PMID 17646360.

^ Sprague ER, Wang C, Baker D, Bjorkman PJ (June 2006). "Crystal structure of the HSV-1 Fc receptor bound to Fc reveals a mechanism for antibody bipolar bridging". PLOS Biology. 4 (6): e148. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040148. PMC 1450327. PMID 16646632.

^ Paulson, Tom (July 19, 2006). "Gates Foundation awards $287 million for HIV vaccine research". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Liu Y, et al. (2007). "Development of IgG1 b12 scaffolds and HIV-1 env-based outer domain immunogens capable of eliciting and detecting IgG1 b12-like antibodies" (PDF). Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2008.

^ Baker D. "David Baker's Rosetta@home journal archives (message 40756)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Homing Endonuclease Genes: New Tools for Mosquito Population Engineering and Control". Grand Challenges in Global Health. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Windbichler N, Papathanos PA, Catteruccia F, Ranson H, Burt A, Crisanti A (2007). "Homing endonuclease mediated gene targeting in Anopheles gambiae cells and embryos". Nucleic Acids Research. 35 (17): 5922–33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm632. PMC 2034484. PMID 17726053.

^ Ashworth J, Havranek JJ, Duarte CM, et al. (June 2006). "Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity". Nature. 441 (7093): 656–59. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..656A. doi:10.1038/nature04818. PMC 2999987. PMID 16738662.

^ Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, Spangler JB, Jude KM, Labão-Almeida C, Ali LR, Quijano-Rubio A, Ruterbusch M, Leung I, Biary T, Crowley SJ, Marcos E, Walkey CD, Weitzner BD, Pardo-Avila F, Castellanos J, Carter L, Stewart L, Riddell SR, Pepper M, Bernardes GJ, Dougan M, Garcia KC, Baker D (January 2019). "De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15". Nature. 565 (7738): 186–191. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7. PMC 6521699. PMID 30626941.

^ "Rosetta's role in fighting coronavirus – Institute for Protein Design". Retrieved March 6, 2020.

^ Simons KT, Bonneau R, Ruczinski I, Baker D (1999). "Ab initio protein structure prediction of CASP III targets using Rosetta". Proteins. Suppl 3: 171–76. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(1999)37:3+<171::AID-PROT21>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10526365.

^ "Interview with David Baker". Team Picard Distributed Computing. 2006. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

^ Nauli S, Kuhlman B, Baker D (July 2001). "Computer-based redesign of a protein folding pathway". Nature Structural Biology. 8 (7): 602–05. doi:10.1038/89638. PMID 11427890.

^ Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D (November 2003). "Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy". Science. 302 (5649): 1364–68. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1364K. doi:10.1126/science.1089427. PMID 14631033.

^ Jones DT (November 2003). "Structural biology. Learning to speak the language of proteins". Science. 302 (5649): 1347–48. doi:10.1126/science.1092492. PMID 14631028.

^ von Grotthuss M, Wyrwicz LS, Pas J, Rychlewski L (June 2004). "Predicting protein structures accurately". Science. 304 (5677): 1597–99, author reply 1597–99. doi:10.1126/science.304.5677.1597b. PMID 15192202.

^ "Articles citing: Kuhlman et al. (2003) 'Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy'". ISI Web of Science. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

^ "October 2005 molecule of the month: Designer proteins". RCSB Protein Data Bank. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Kuhlman laboratory homepage". Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "RosettaDesign web server". Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Jump up to: a b Gray JJ, Moughon SE, Kortemme T, et al. (July 2003). "Protein–protein docking predictions for the CAPRI experiment". Proteins. 52 (1): 118–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.80.9354. doi:10.1002/prot.10384. PMID 12784377.

^ Daily MD, Masica D, Sivasubramanian A, Somarouthu S, Gray JJ (2005). "CAPRI rounds 3–5 reveal promising successes and future challenges for RosettaDock". Proteins. 60 (2): 181–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.521.9981. doi:10.1002/prot.20555. PMID 15981262. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012.

^ Méndez R, Leplae R, Lensink MF, Wodak SJ (2005). "Assessment of CAPRI predictions in rounds 3–5 shows progress in docking procedures". Proteins. 60 (2): 150–69. doi:10.1002/prot.20551. PMID 15981261. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012.

^ "RosettaDock server". Rosetta Commons. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

^ "Protein–protein docking at Rosetta@home". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Robetta web server". Baker laboratory. University of Washington. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

^ Aloy P, Stark A, Hadley C, Russell RB (2003). "Predictions without templates: new folds, secondary structure, and contacts in CASP5". Proteins. 53 Suppl 6: 436–56. doi:10.1002/prot.10546. PMID 14579333.

^ Tress M, Ezkurdia I, Graña O, López G, Valencia A (2005). "Assessment of predictions submitted for the CASP6 comparative modeling category". Proteins. 61 Suppl 7: 27–45. doi:10.1002/prot.20720. PMID 16187345.

^ Battey JN, Kopp J, Bordoli L, Read RJ, Clarke ND, Schwede T (2007). "Automated server predictions in CASP7". Proteins. 69 Suppl 8: 68–82. doi:10.1002/prot.21761. PMID 17894354.

^ Chivian D, Kim DE, Malmström L, Schonbrun J, Rohl CA, Baker D (2005). "Prediction of CASP6 structures using automated Robetta protocols". Proteins. 61 Suppl 7: 157–66. doi:10.1002/prot.20733. PMID 16187358.

^ Baker D. "David Baker's Rosetta@home journal, message 52902". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Ovchinnikov, S; Kim, DE; Wang, RY; Liu, Y; DiMaio, F; Baker, D (September 2016). "Improved de novo structure prediction in CASP11 by incorporating coevolution information into Rosetta". Proteins. 84 Suppl 1: 67–75. doi:10.1002/prot.24974. PMC 5490371. PMID 26677056.

^ Baker D. "David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 52963)". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

^ "Foldit forums: How many users does Foldit have? Etc. (message 2)". University of Washington. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

^ "Foldit: Frequently Asked Questions". fold.it. University of Washington. Retrieved September 19,2008.

^ "Project list – BOINC". University of California. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

^ Pande Group (2010). "High Performance FAQ". Stanford University. Archived from the original (FAQ) on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

^ 7im (April 2, 2010). "Re: Answers to: Reasons for not using F@H". Retrieved September 19,2011.

^ Vijay Pande (August 5, 2011). "Results page updated – new key result published in our work in Alzheimer's Disease". Retrieved September 19, 2011.

^ Pande Group. "Folding@home Diseases Studied FAQ". Stanford University. Archived from the original (FAQ) on October 11, 2007. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

^ Vijay Pande (September 26, 2007). "How FAH works: Molecular dynamics". Retrieved September 10, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b tjlane (June 9, 2011). "Re: Course grained Protein folding in under 10 minutes". Retrieved September 19, 2011.

^ jmn (July 29, 2011). "Rosetta@home and Folding@home: additional projects". Retrieved September 19, 2011.

^ Pande Group. "Client Statistics by OS". Stanford University. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b "Rosetta@home: Credit overview". boincstats.com. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

^ Malmström L, Riffle M, Strauss CE, et al. (April 2007). "Superfamily assignments for the yeast proteome through integration of structure prediction with the gene ontology". PLOS Biology. 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050076. PMC 1828141. PMID 17373854.

^ Bonneau R (2006). "World Community Grid Message Board Posts: HPF -> HPF2 transition". Bonneau Lab, New York University. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "List of Richard Bonneau's publications". Bonneau Lab, New York University. Archived from the original on July 7, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ Bonneau R. "World Community Grid Message Board Posts". Bonneau Lab, New York University. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Predictor@home: Developing new application areas for P@H". The Brooks Research Group. Retrieved September 7, 2008.[dead link]

^ Carrillo-Tripp M (2007). "dTASSER". The Scripps Research Institute. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "RALPH@home website". RALPH@home forums. University of Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home". Retrieved March 19, 2020.

^ "Rosetta@home: The new credit system explained". Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

^ "BOINCstats: Project Credit Comparison". boincstats.com. 2008. Archived from the originalon September 13, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

^ "Credit divided over projects". boincstats.com. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

^ "Rosetta@home: Predictor of the day archive". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

^ "Rosetta@home: Protein Folding, Design, and Docking". Rosetta@home. University of Washington. 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

External links[edit]

Official website

Baker Lab Baker Lab website

David Baker's Rosetta@home journal

BOINC Includes platform overview, and a guide to install BOINC and attach to Rosetta@home

BOINCstats – Rosetta@home Detailed contribution statistics

RALPH@home Website for Rosetta@home alpha testing project

Rosetta@home video on YouTube Overview of Rosetta@home given by David Baker and lab members

Rosetta Commons Academic collaborative for developing the Rosetta platform

Kuhlman lab webpage, home of RosettaDesign

Online Rosetta services

Rosetta Commons list of available servers

Robetta Protein structure prediction server

ROSIE Docking, design, etc. multifunctional server-set

RosettaDesign Protein design server

RosettaBackrub Flexible backbone / protein design server

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)