Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has many variants; some are believed or have been believed to be of particular importance due to their potential for increased transmissibility,[1] increased virulence, or reduced effectiveness of vaccines against them.[2][3] This article discusses such notable variants of SARS-CoV-2 and notable missense mutations found in these variants.

Play media

Play mediaPositive, negative, and neutral mutations during the evolution of coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2.

According to one source (Zhukova et al.), the sequence WIV04/2019, belonging to the GISAID S clade / PANGO A lineage / Nextstrain 19B clade, is thought to most closely reflect the sequence of the original virus infecting humans—known as "sequence zero".[4] WIV04/2019 was sampled from a symptomatic patient on 30 December 2019 and is widely used (especially by those collaborating with GISAID)[5] as a reference sequence.[4] However, another group (Sudhir Kumar et al.)[6] refer extensively to an NCBI reference genome (GenBankID:NC_045512; GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_402125),[7] this sample was collected on 26 December 2019,[8] although they also used the WIV04 GISAID reference genome (ID: EPI_ISL_402124),[9] in their analyses.[10] The earliest sequence, Wuhan-1, was collected on 24 December 2019.[6]

OverviewEdit

Though the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 may have resulted from recombination events between bat-SARS-like-CoV-2 and a pangolin coronavirus (through cross-species transmission),[11] mutations have been shown to play an important role in the ongoing evolution and emergence of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants.[1]

The variant first sampled and identified in China is considered by researchers to differ from the progenitor genome "by three variants."[6][12] Therefore, there are many lineages of SARS-CoV-2.[13]

The following table presents information and level of risk for variants with elevated or possibly elevated risk at present[14][15][16][17] or in the past. The intervals assume a 95% confidence or credibility level, unless otherwise stated.

First detectionSpreadIdentificationNotable mutationsClinical changes relative to the variant first identified in Wuhan[A]

LocationsDate[inconsistent]PANGO lineage[13]Nextstrain clade[18][14]PHE variant[B]Other namesTransmissibilityVirulenceAntigenicity

United Kingdom Feb 2020[13][dubious – discuss] Global B.1.1.7 20I/501Y.V1 VOC-20DEC-01[C] — N501Y, 69–70del, P681H[19][20] ≈74% higher[21] ≈61% (42–82%) more lethal[22][D] No change[24]

United Kingdom Feb 2020[13][dubious – discuss] Global B.1.1.7 20I/501Y.V1 VOC-20DEC-01[C] — N501Y, 69–70del, P681H[19][20] ≈74% higher[21] ≈61% (42–82%) more lethal[22][D] No change[24] Nigeria Aug 2020[25] Global B.1.1.207 — — — P681H[19] No evidence of change[26] No evidence of change[26] Under investigation

Nigeria Aug 2020[25] Global B.1.1.207 — — — P681H[19] No evidence of change[26] No evidence of change[26] Under investigation United States June 2020[27] Global B.1.429, B.1.427[17] 20C/S:452R — CAL.20C[28] I4205V, D1183Y, S13I, W152C, L452R ≈20% (18.6%–24.2%) higher[14][29] Under investigation Moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralising antibodies[30]

United States June 2020[27] Global B.1.429, B.1.427[17] 20C/S:452R — CAL.20C[28] I4205V, D1183Y, S13I, W152C, L452R ≈20% (18.6%–24.2%) higher[14][29] Under investigation Moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralising antibodies[30] Denmark Sep 2020[31] Likely extinct Not registered Cluster 5, ΔFVI-spike[32] Y453F, 69–70deltaHV[32] — Moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralising antibodies[31]

Denmark Sep 2020[31] Likely extinct Not registered Cluster 5, ΔFVI-spike[32] Y453F, 69–70deltaHV[32] — Moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralising antibodies[31] South Africa Oct 2020[19] Global B.1.351 20H/501Y.V2 VOC-20DEC-02 501Y.V2[24] N501Y, K417N, E484K[19] ≈50% (20–113%) higher[24] No evidence of change[26] Significant reduction in neutralisation by antibodies[33][34]

South Africa Oct 2020[19] Global B.1.351 20H/501Y.V2 VOC-20DEC-02 501Y.V2[24] N501Y, K417N, E484K[19] ≈50% (20–113%) higher[24] No evidence of change[26] Significant reduction in neutralisation by antibodies[33][34] India Oct 2020[35] Global B.1.617 (B.1.617.1, B.1.617.2, B.1.617.3) 20A[36][E] VUI-21APR-01, VOC-21APR-02,[F] VUI-21APR-03 — E484Q, L452R, P681R[37] Potentially ≈120% higher[38][better source needed] Under investigation Slight reduction in effective neutralisation[39]

India Oct 2020[35] Global B.1.617 (B.1.617.1, B.1.617.2, B.1.617.3) 20A[36][E] VUI-21APR-01, VOC-21APR-02,[F] VUI-21APR-03 — E484Q, L452R, P681R[37] Potentially ≈120% higher[38][better source needed] Under investigation Slight reduction in effective neutralisation[39] Japan

Japan Brazil Dec 2020[40] Global P.1 20J/501Y.V3 VOC-21JAN-02 B.1.1.28.1[41][17] N501Y, E484K, K417T[19] ≈161% (145–176%) higher[42][G] ≈80% (50% CrI, 40–120%) more lethal[43][H] Overall reduction in effective neutralisation[24]

Brazil Dec 2020[40] Global P.1 20J/501Y.V3 VOC-21JAN-02 B.1.1.28.1[41][17] N501Y, E484K, K417T[19] ≈161% (145–176%) higher[42][G] ≈80% (50% CrI, 40–120%) more lethal[43][H] Overall reduction in effective neutralisation[24] United Kingdom

United Kingdom Nigeria Dec 2020[44] Global B.1.525 20C[I] VUI-21FEB-03[J] — E484K, F888L[45] Under investigation Under investigation Possibly reduced neutralisation[14]

Nigeria Dec 2020[44] Global B.1.525 20C[I] VUI-21FEB-03[J] — E484K, F888L[45] Under investigation Under investigation Possibly reduced neutralisation[14] United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States Feb 2021[46] International B.1.1.7 with E484K[46] 20I/501Y.V1/S:E484K VOC-21FEB-02[46][K] B.1.1.7+E484K[47] N501Y, 69–70del, P681H,[19][20] E484K Under investigation Under investigation Under investigation

United States Feb 2021[46] International B.1.1.7 with E484K[46] 20I/501Y.V1/S:E484K VOC-21FEB-02[46][K] B.1.1.7+E484K[47] N501Y, 69–70del, P681H,[19][20] E484K Under investigation Under investigation Under investigation^ "—" denotes that no reliable sources could be found to cite.

^ The naming format was updated in March 2021, changing the year from 4 to 2 digits and the month from 2 digits to a 3-letter abbreviation. For example, VOC-202101-02 became VOC-21JAN-02.[15]

^ B.1.1.7 with E484K is separately designated VOC-21FEB-02

^ Another study[23] has estimated that B.1.1.7 may be 32–104% more lethal

^ Includes B.1.617, B.1.617.1, B.1.617.2, and B.1.617.3[14]

^ Formerly VUI-21APR-02.

^ Another preliminary study[43] has estimated that P.1 may be 170–240% more transmissible, with a credible interval with a low probability of 50%.[better source needed]

^ The reported credible interval has a low probability of only 50%, so the estimated lethality can only be understood as possible, not certain nor likely.

^ Includes B.1.525 and B.1.526.[14]

^ Formerly UK1188.

^ Alternatively VOC-202102/02

NomenclatureEdit

SARS-CoV-2 corresponding nomenclatures[48]PANGO lineages[49]Notes to PANGO lineages[50]Nextstrain clades,[51] 2021[52]GISAID cladesNotable variants

A.1–A.6 19B S contains "reference sequence" WIV04/2019[4]

B.3–B.7, B.9, B.10, B.13–B.16 19A L

O[a]

B.2 V

B.1 B.1.5–B.1.72 20A G Lineage B.1 in the PANGO Lineages nomenclature system; includes B.1.617[36]

B.1.9, B.1.13, B.1.22, B.1.26, B.1.37 GH

B.1.3–B.1.66 20C Includes Lineage B.1.429 / CAL.20C[53] and Lineage B.1.525[14]

20G Predominant in US generally, Jan '21[53]

20H Includes B.1.351 aka 20H/501Y.V2 or 501.V2 lineage

B.1.1 20B GR Includes B.1.1.207[citation needed]

20D

20J Includes P.1 and P.2[54][55]

20F

20I Includes lineage B.1.1.7 aka VOC-202012/01, VOC-20DEC-01 or 20I/501Y.V1

B.1.177 20E (EU1)[52] GV[a] Derived from 20A[52]

No consistent nomenclature has been established for SARS-CoV-2.[57] Colloquially, including by governments and news organizations, concerning variants are often referred to by the country in which they were first identified,[58][59][60] but as of January 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) is working on "standard nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 variants that does not reference a geographical location" and "avoids stigmatization and is geographically and politically neutral."[61]

While there are many thousands of variants of SARS-CoV-2,[62] subtypes of the virus can be put into larger groupings such as lineages or clades.[b] Three main, generally used nomenclatures[57] have been proposed:

As of January 2021, GISAID – referring to SARS-CoV-2 as hCoV-19[50] – had identified eight global clades (S, O, L, V, G, GH, GR, and GV).[63]

In 2017, Hadfield et al. announced Nextstrain, intended "for real-time tracking of pathogen evolution".[64] Nextstrain has later been used for tracking SARS-CoV-2, identifying 11 major clades[c] (19A, 19B, and 20A–20I) as of January 2021.[51]

In 2020, Rambaut et al. of the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages (PANGOLIN)[65] software team proposed in an article[49] "a dynamic nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 lineages that focuses on actively circulating virus lineages and those that spread to new locations";[57] as of February 2021, six major lineages (A, B, B.1, B.1.1, B.1.177, B.1.1.7) had been identified.[13][66]

Each national public health institute may also institute its own nomenclature system for the purposes of tracking specific variants. For example, Public Health England designated each tracked variant by year, month and number in the format [YYYY] [MM]/[NN], prefixing 'VUI' or 'VOC' for a variant under investigation or a variant of concern respectively.[15] This system has now been modified and now uses the format [YY] [MMM]-[NN], where the month is written out using a three-letter code.[15]

Criteria for notabilityEdit

Viruses generally acquire mutations over time, giving rise to new variants. When a new variant appears to be growing in a population, it can be labeled as an "emerging variant".

Some of the potential consequences of emerging variants are the following:[19][67]

Increased transmissibility

Increased morbidity

Increased mortality

Ability to evade detection by diagnostic tests

Decreased susceptibility to antiviral drugs (if and when such drugs are available)

Decreased susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies, either therapeutic (e.g., convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibodies) or in laboratory experiments

Ability to evade natural immunity (e.g., causing reinfections)

Ability to infect vaccinated individuals

Increased risk of particular conditions such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome or long-haul COVID.

Increased affinity for particular demographic or clinical groups, such as children or immunocompromised individuals.

Variants that appear to meet one or more of these criteria may be labeled "variants under investigation" or "variants of interest" pending verification and validation of these properties. The primary characteristic of a variant of interest is that it shows evidence that demonstrates it is the cause of an increased proportion of cases or unique outbreak clusters; however, it must also have limited prevalence or expansion at national levels, or the classification would be elevated to a "variant of concern".[15][68] If there is clear evidence that the effectiveness of prevention or intervention measures for a particular variant is substantially reduced, that variant is termed a "variant of high consequence".[14]

Notable variantsEdit

Cluster 5Edit

Main article: Cluster 5

In early November 2020, Cluster 5, also referred to as ΔFVI-spike by the Danish State Serum Institute (SSI),[32] was discovered in Northern Jutland, Denmark, and is believed to have been spread from minks to humans via mink farms. On 4 November 2020, it was announced that the mink population in Denmark would be culled to prevent the possible spread of this mutation and reduce the risk of new mutations happening. A lockdown and travel restrictions were introduced in seven municipalities of Northern Jutland to prevent the mutation from spreading, which could compromise national or international responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. By 5 November 2020, some 214 mink-related human cases had been detected.[69]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that cluster 5 has a "moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies".[31] SSI warned that the mutation could reduce the effect of COVID-19 vaccines under development, although it was unlikely to render them useless. Following the lockdown and mass-testing, SSI announced on 19 November 2020 that cluster 5 in all probability had become extinct.[70] As of 1 February 2021, authors to a peer-reviewed paper, all of whom were from the SSI, assessed that cluster 5 was not in circulation in the human population.[71]

Lineage B.1.1.7 / Variant of Concern 20DEC-01Edit

Main article: Lineage B.1.1.7

False-colour transmission electron micrograph of a B.1.1.7 variant coronavirus. The variant's increased transmissibility is believed to be due to changes in structure of the spike proteins, shown here in green.

First detected in October 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom from a sample taken the previous month in Kent,[72] Lineage B.1.1.7,[73] was previously known as the first Variant Under Investigation in December 2020 (VUI – 202012/01)[74] and later notated as VOC-202012/01.[15] It is also known as lineage B.1.1.7 or 20I/501Y.V1 (formerly 20B/501Y.V1).[75][76][19] Since then, its prevalence odds have doubled every 6.5 days, the presumed generational interval.[77][78] It is correlated with a significant increase in the rate of COVID-19 infection in United Kingdom, associated partly with the N501Y mutation.[79] There is some evidence that this variant has 40–80% increased transmissibility (with most estimates lying around the middle to higher end of this range),[80] and early analyses suggest an increase in lethality.[81][82] More recent work has found no evidence of increased virulence. [83] As of May 2021, Lineage B.1.1.7 has been detected in some 120 countries.[84]

Variant of Concern 21FEB-02Edit

Variant of Concern 21FEB-02 (previously written as VOC-202102/02), described by Public Health England (PHE) as "B.1.1.7 with E484K"[15] is of the same lineage in the Pango nomenclature system, but has an additional E484K mutation. As of 17 March 2021, there are 39 confirmed cases of VOC-21FEB-02 in the UK.[15] On 4 March 2021, scientists reported B.1.1.7 with E484K mutations in the state of Oregon. In 13 test samples analysed, one had this combination, which appeared to have arisen spontaneously and locally, rather than being imported.[85][86][87]

Lineage B.1.1.207Edit

First sequenced in August 2020 in Nigeria,[88] the implications for transmission and virulence are unclear but it has been listed as an emerging variant by the US Centers for Disease Control.[19] Sequenced by the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases in Nigeria, this variant has a P681H mutation, shared in common with UK's Lineage B.1.1.7. It shares no other mutations with Lineage B.1.1.7 and as of late December 2020 this variant accounts for around 1% of viral genomes sequenced in Nigeria, though this may rise.[88] As of May 2021, Lineage B.1.1.207 has been detected in 10 countries.[25]

Lineage B.1.1.317Edit

While B.1.1.317 is not considered a variant of concern, Queensland Health forced 2 people undertaking hotel quarantine in Brisbane, Australia to undergo an additional 5 days quarantine on top of the mandatory 14 days after it was confirmed they were infected with this variant.[89]

Lineage B.1.1.318Edit

Lineage B.1.1.318 was designated by PHE as a VUI (VUI-21FEB-04,[15] previously VUI-202102/04) on 24 February 2021. 16 cases of it have been detected in the UK.[15][90]

Lineage B.1.351Edit

Main article: Lineage B.1.351

On 18 December 2020, the 501.V2 variant, also known as 501.V2, 20H/501Y.V2 (formerly 20C/501Y.V2), VOC-20DEC-02 (formerly VOC-202012/02), or lineage B.1.351,[19] was first detected in South Africa and reported by the country's health department.[91] Researchers and officials reported that the prevalence of the variant was higher among young people with no underlying health conditions, and by comparison with other variants it is more frequently resulting in serious illness in those cases.[92][93] The South African health department also indicated that the variant may be driving the second wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in the country due to the variant spreading at a more rapid pace than other earlier variants of the virus.[91][92]

Scientists noted that the variant contains several mutations that allow it to attach more easily to human cells because of the following three mutations in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) in the spike glycoprotein of the virus: N501Y,[91][94] K417N, and E484K.[95][96] The N501Y mutation has also been detected in the United Kingdom.[91][97]

Lineage B.1.429 / CAL.20CEdit

Lineage B.1.429, also known as CAL.20C, is defined by five distinct mutations (I4205V and D1183Y in the ORF1ab-gene, and S13I, W152C, L452R in the spike protein's S-gene), of which the L452R (previously also detected in other unrelated lineages) was of particular concern.[53][98] B.1.429 is possibly more transmissible, but further study is necessary to confirm this.[98] CDC has listed B.1.429 and the related B.1.427 as "variants of concern," and cites a preprint for saying that they exhibit a ~20% increase in viral transmissibility, have a "Significant impact on neutralization by some, but not all," therapeutics that have been given Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by FDA for treatment or prevention of COVID-19, and moderately reduce neutralization by plasma collected by people who have previously infected by the virus or who have received a vaccine against the virus.[99][100]

B.1.429 was first observed in July 2020 by researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California, in one of 1,230 virus samples collected in Los Angeles County since the start of the COVID-19 epidemic.[101] It was not detected again until September when it reappeared among samples in California, but numbers remained very low until November.[102][103] In November 2020, the CAL.20C variant accounted for 36 percent of samples collected at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and by January 2021, the CAL.20C variant accounted for 50 percent of samples.[98] In a joint press release by University of California, San Francisco, California Department of Public Health, and Santa Clara County Public Health Department,[104] the variant was also detected in multiple counties in Northern California. From November to December 2020, the frequency of the variant in sequenced cases from Northern California rose from 3% to 25%.[105] In a preprint, CAL.20C is described as belonging to clade 20C and contributing approximately 36% of samples, while an emerging variant from the 20G clade accounts for some 24% of the samples in a study focused on Southern California. Note however that in the US as a whole, the 20G clade predominates, as of January 2021.[53] Following the increasing numbers of CAL.20C in California, the variant has been detected at varying frequencies in most US states. Small numbers have been detected in other countries in North America, and in Europe, Asia and Australia.[102][103] After an initial increase, its frequency rapidly dropped from February 2021 as it was being outcompeted by the more transmissible B.1.1.7. In April, B.1.429 remained relatively frequent in parts of northern California, but it had virtually disappeared from the south of the state and had never been able to establish a foothold elsewhere; only 3.2% of all cases in the United States were B.1.429, whereas more than two-thirds were B.1.1.7.[106]

Lineage B.1.525Edit

B.1.525, also called VUI-21FEB-03[15] (previously VUI-202102/03) by Public Health England (PHE) and formerly known as UK1188,[15] does not carry the same N501Y mutation found in B.1.1.7, 501.V2 and P.1, but carries the same E484K-mutation as found in the P.1, P.2, and 501.V2 variants, and also carries the same ΔH69/ΔV70 deletion (a deletion of the amino acids histidine and valine in positions 69 and 70) as found in B.1.1.7, N439K variant (B.1.141 and B.1.258) and Y453F variant (Cluster 5).[107] B.1.525 differs from all other variants by having both the E484K-mutation and a new F888L mutation (a substitution of phenylalanine (F) with leucine (L) in the S2 domain of the spike protein). As of March 5, it had been detected in 23 countries, including the UK, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Nigeria, Ghana, Jordan, Japan, Singapore, Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Austria, Malaysia, Switzerland, the Republic of Ireland and the US.[108][109][110][45][111][112][113] It has also been reported in Mayotte, the overseas department/region of France.[108] The first cases were detected in December 2020 in the UK and Nigeria, and as of 15 February, it had occurred in the highest frequency among samples in the latter country.[45] As of 24 February, 56 cases were found in the UK.[15] Denmark, which sequences all its COVID-19 cases, found 113 cases of this variant from January 14 to February 21, of which seven were directly related to foreign travels to Nigeria.[109]

UK experts are studying it to understand how much of a risk it could be. It is currently regarded as a "variant under investigation", but pending further study, it may become a "variant of concern". Prof Ravi Gupta, from the University of Cambridge spoke to the BBC and said B.1.525 appeared to have "significant mutations" already seen in some of the other newer variants, which is partly reassuring as their likely effect is to some extent more predictable.[44]

Lineage B.1.526Edit

Main article: Lineage B.1.526

In November 2020, a mutant variant was discovered in New York City, which was named B.1.526.[114] As of April 11, 2021, the variant has been detected in at least 48 U.S. states and 18 countries. In a pattern mirroring B.1.429 of California, B.1.526 was initially able to reach relatively high levels in some states, but in the spring of 2021 it was outcompeted by the more transmissible B.1.1.7.[106]

Lineage B.1.617Edit

Main article: Lineage B.1.617

In October 2020, a new variant was discovered in India, which was named B.1.617. There were very few detections until January 2021 but by April it had spread to at least 20 countries;[115][116][117] by early May it had been detected in about 50 countries and on all continents except Antartica.[118] Among some 15 defining mutations, it has spike mutations D111D (synonymous substitution), G142D,[119] P681R, E484Q[120] and L452R,[121] the latter two of which may cause it to easily avoid antibodies.[122] In an announcement on 15 April 2021, Public Health England (PHE) designated B.1.617 as a 'Variant under investigation', VUI-21APR-01.[123] On 29 April 2021, PHE added two further variants, VUI-21APR-02 and VUI-21APR-03, effectively B.1.617.2 and B.1.617.3.[124] British scientists declared B.1.617.2 (which notably lacks mutation at E484Q) as a "variant of concern", after they flagged evidence that it spreads more quickly than the original version of the virus.[125][126]

Lineage B.1.618Edit

In October 2020, this variant was first isolated. It has a mutation called E484K which is the same mutation which South African variant has. It is growing significantly in recent months in West Bengal.[127][128] As of 23 April 2021, the CoV-Lineages database showed 135 sequences detected in India, with single-figure numbers in each of eight other countries worldwide.[129]

Lineage B.1.620Edit

In March 2021, this variant was discovered in Lithuania, it was named B.1.620[citation needed] also known as Lithuanian strain. For now, scientists have found that this lineage contains an E484 mutation.[130]

Lineage P.1Edit

Main article: Lineage P.1

Lineage P.1, termed Variant of Concern 21JAN-02[15] (formerly VOC-202101/02) by Public Health England[15] and 20J/501Y.V3 by Nextstrain,[14] was detected in Tokyo on 6 January 2021 by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID). The new lineage was first identified in four people who arrived in Tokyo having travelled from the Brazilian Amazonas state on 2 January 2021.[131] On 12 January 2021, the Brazil-UK CADDE Centre confirmed 13 local cases of the P.1 new lineage in the Amazon rain forest.[132] This variant of SARS-CoV-2 has been named P.1 lineage (although it is a descendant of B.1.1.28, the name B.1.1.28.1 is not permitted and thus the resultant name is P.1), and has 17 unique amino acid changes, 10 of which in its spike protein, including the three concerning mutations: N501Y, E484K and K417T.[132][133][134][135]:Figure 5

The N501Y and E484K mutations favour the formation of a stable RBD-hACE2 complex, thus, enhancing the binding affinity of RBD to hACE2. However, the K417T mutation disfavours complex formation between RBD and hACE2, which has been demonstrated to reduce the binding affinity.[1]

The new lineage was absent in samples collected from March to November 2020 in Manaus, Amazonas state, but it was detected for the same city in 42% of the samples from 15–23 December 2020, followed by 52.2% during 15–31 December and 85.4% during 1–9 January 2021.[132] A separate Brazilian study identified another sub-lineage of the B.1.1.28 lineage circulating in the state of Rio de Janeiro, now named P.2 lineage,[136] that harbours the E484K mutation but not the N501Y and K417T mutation.[135] The P.2 lineage evolved independently in Rio de Janeiro without being directly related to the P.1 lineage from Manaus.[132]

A study found that P.1 infections can produce nearly ten times more viral load compared to persons infected by one of the other Brazilian lineages (B.1.1.28 or B.1.195). P.1 also showed 2.2 times higher transmissibility with the same ability to infect both adults and older persons, suggesting P.1 lineages are more successful at infecting younger humans irrespective of sex.[137]

A study of samples collected in Manaus between November 2020 and January 2021, indicated the P.1 lineage to be 1.4–2.2 times more transmissible and was shown to be capable of evading 25–61% of inherited immunity from previous coronavirus diseases, leading to the possibility of reinfection after recovery from an earlier COVID-19 infection. As for the fatality ratio, P.1 infections were also found to be 10–80% more lethal.[138][139][43]

A study found that people fully vaccinated with Pfizer or Moderna have significantly decreased neutralization effect against P.1, although the actual impact on the course of the disease is uncertain.[140] A pre-print study by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation published in early April found that the real-world performance of people with the initial dose of the Sinovac's Coronavac Vaccine had approximately 50% efficacy rate. They expected the efficacy to be higher after the 2nd dose. The study is ongoing.[141]

Preliminary data from two studies indicate that the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine is effective against the P.1 variant, although the exact level of efficacy has not yet been released.[142][143] Preliminary data from a study conducted by Instituto Butantan suggest that CoronaVac is effective against the P.1 variant as well, and the study will be expanded to obtain definitive data.[144]

Lineage P.3Edit

Main article: Lineage P.3

On 18 February 2021, the Department of Health of the Philippines confirmed the detection of two mutations of COVID-19 in Central Visayas after samples from patients were sent to undergo genome sequencing. The mutations were later named as E484K and N501Y, which were detected in 37 out of 50 samples, with both mutations co-occurrent in 29 out of these. There were no official names for the variants and the full sequence was yet to be identified.[145]

On 13 March, the Department of Health confirmed the mutations constitutes a variant which was designated as lineage P.3.[146] On the same day, it also confirmed the first Lineage P.1 COVID-19 case in the country. Although the P.1 and P.3 variants stem from the same lineage B.1.1.28, the department said that P.3 variant's impact on vaccine efficacy and transmissibility is yet to be ascertained. The Philippines had 98 cases of P.3 variant on 13 March.[147] On 12 March it was announced that P.3 had also been detected in Japan.[148][149] On 17 March, the United Kingdom confirmed its first two cases,[150] where PHE termed it VUI-21MAR-02.[15] On 30 April 2021, Malaysia detected 8 cases of P.3 variant in Sarawak.[151]

Notable missense mutationsEdit

N440KEdit

This mutation has been observed in cell cultures to be 10 times more infective compared to the previously widespread A2a strain and 1000 times more in the lesser widespread A3i strain.[152] It is involved in current rapid surges of Covid cases in India.[153] India has the largest proportion of N440K mutated variants followed by the US and Germany.[154]

L452REdit

The name of the mutation, L452R, refers to an exchange whereby the leucine (L) is replaced by arginine (R) at position 452.[155]

There has been a significant surge of COVID-19 starting 2021 all across India caused in part by B.1.617, frequently, but misleadingly, referred to as a "double mutant". L452R is a relevant mutation in this strain that enhances ACE2 receptor binding ability and can reduce vaccine-stimulated antibodies from attaching to this altered spike protein.

L452R, some studies show, could even make the coronavirus resistant to T cells, that are class of cells necessary to target and destroy virus-infected cells. They are different from antibodies that are useful in blocking coronavirus particles and preventing it from proliferating.[116]

S477G/NEdit

A highly flexible region in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2, starting from residue 475 and continuing up to residue 485, was identified using bioinformatics and statistical methods in several studies. The University of Graz[156] and the Biotech Company Innophore[157] have shown in a recent publication that structurally, the position S477 shows the highest flexibility among them.[158]

At the same time, S477 is hitherto the most frequently exchanged amino acid residue in the RBDs of SARS-CoV-2 mutants. By using molecular dynamics simulations of RBD during the binding process to hACE2, it has been shown that both S477G and S477N strengthen the binding of the SARS-COV-2 spike with the hACE2 receptor. The vaccine developer BioNTech[159] referenced this amino acid exchange as relevant regarding future vaccine design in a preprint published in February 2021.[160]

E484KEdit

The name of the mutation, E484K, refers to an exchange whereby the glutamic acid (E) is replaced by lysine (K) at position 484.[155] It is nicknamed "Eeek".[161]

E484K has been reported to be an escape mutation (i.e., a mutation that improves a virus's ability to evade the host's immune system[162][163]) from at least one form of monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2, indicating there may be a "possible change in antigenicity".[164] The P.1. lineage described in Japan and Manaus,[132] the P.2 lineage (also known as B.1.1.28.2 lineage, Brazil)[135] and 501.V2 (South Africa) exhibit this mutation.[164] A limited number of B.1.1.7 genomes with E484K mutation have also been detected.[165] Monoclonal and serum-derived antibodies are reported to be from 10 to 60 times less effective in neutralizing virus bearing the E484K mutation.[166][40] On 2 February 2021, medical scientists in the United Kingdom reported the detection of E484K in 11 samples (out of 214,000 samples), a mutation that may compromise current vaccine effectiveness.[167][168]

E484QEdit

The name of the mutation, E484Q, refers to an exchange whereby the glutamic acid (E) is replaced by glutamine (Q) at position 484.[155]

India is seeing a significant surge of COVID-19 starting 2021 caused in part by B.1.617. This has frequently (but misleadingly, as most variants contain multiple mutations) been referred to as a "double mutant".[169] E484Q may enhance ACE2 receptor binding ability and may reduce vaccine-stimulated antibodies from attaching to this altered spike protein.[116]

N501YEdit

N501Y denotes a change from asparagine (N) to tyrosine (Y) in amino-acid position 501.[170] N501Y has been nicknamed "Nelly".[161]

This change is believed by PHE to increase binding affinity because of its position inside the spike glycoprotein's receptor-binding domain, which binds ACE2 in human cells; data also support the hypothesis of increased binding affinity from this change.[20] Molecular interaction modeling and the free energy of binding calculations has demonstrated that the mutation N501Y has the highest binding affinity in variants of concern RBD to hACE2.[1] Variants with N501Y include P.1 (Brazil/Japan),[164][132] Variant of Concern 20DEC-01 (UK), 501.V2 (South Africa), and COH.20G/501Y (Columbus, Ohio).[1] This last became the dominant form of the virus in Columbus in late December 2020 and January and appears to have evolved independently of other variants.[171][172]

D614GEdit

Logarithmic Prevalence of D614G in 2020 according to sequences in the GISAID database[173]

D614G is a missense mutation that affects the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The frequency of this mutation in the viral population has increased during the pandemic. G (glycine) has replaced D (aspartic acid) at position 614 in many countries, especially in Europe though more slowly in China and the rest of East Asia, supporting the hypothesis that G increases the transmission rate, which is consistent with higher viral titers and infectivity in vitro.[4] Researchers with the PANGOLIN tool nicknamed this mutation "Doug".[161]

In July 2020, it was reported that the more infectious D614G SARS-CoV-2 variant had become the dominant form in the pandemic.[174][175][176][177] PHE confirmed that the D614G mutation had a "moderate effect on transmissibility" and was being tracked internationally.[170]

The global prevalence of D614G correlates with the prevalence of loss of smell (anosmia) as a symptom of COVID-19, possibly mediated by higher binding of the RBD to the ACE2 receptor or higher protein stability and hence higher infectivity of the olfactory epithelium.[178]

Variants containing the D614G mutation are found in the G clade by GISAID[4] and the B.1 clade by the PANGOLIN tool.[4]

P681HEdit

Logarithmic Prevalence of P681H in 2020 according to sequences in the GISAID database[173]

In January 2021, scientists reported in a preprint that the mutation 'P681H', a characteristic feature of the significant novel SARS-CoV-2 variants detected in the U.K. (B.1.1.7) and Nigeria (B.1.1.207), is showing a significant exponential increase in worldwide frequency, similar to the now globally prevalent 'D614G'.[179][173]

P681REdit

The name of the mutation, P681R, refers to an exchange whereby the proline (P) is replaced by arginine (R) at position 681.[155]

Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genomics Consortium (INSACOG) found that other than the two mutations E484Q and L452R, there is also a third significant mutation, P681R in B.1.617. All three concerning mutations are on the spike protein, the operative part of the coronavirus that binds to receptor cells of the body.[116]

A701VEdit

According to initial media reports, the Malaysian Ministry of Health announced on 23 December 2020 that it had discovered a mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 genome which they designated as A701B(sic), among 60 samples collected from the Benteng Lahad Datu cluster in Sabah. The mutation was characterized as being similar to the one found recently at that time in South Africa, Australia, and the Netherlands, although it was uncertain if this mutation was more infectious or aggressive[clarification needed] than before.[180] The provincial government of Sulu in neighboring Philippines temporarily suspended travel to Sabah in response to the discovery of 'A701B' due to uncertainty over the nature of the mutation.[181]

On 25 December 2020, the government health organisation 'Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia/ covid-19 Malaysia' described a mutation A701V as circulating and present in 85% of cases (D614G was present in 100% of cases) in Malaysia.[182][183][184] These reports also referred to samples collected from the Benteng Lahad Datu cluster.[184][183] The text of the announcement was mirrored verbatim on the Facebook page of Noor Hisham Abdullah, Malay Director-General of Health, who was quoted in some of the news articles.[183]

The A701V mutation has the amino acid alanine substituted by valine at position 701 in the spike protein. Globally, South Africa, Australia, Netherlands and England also reported A701V at about the same time as Malaysia.[182] In GISAID, the prevalence of this mutation is found to be about 0.18%. of cases.[182]

On 14 April 2021, 'Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia' reported that the third wave, which had started in Sabah, has involved the introduction of variants with D614G and A701V mutations.[185]

New variant detection and assessmentEdit

On 26 January 2021, the British government said it would share its genomic sequencing capabilities with other countries in order to increase the genomic sequencing rate and trace new variants, and announced a "New Variant Assessment Platform".[186] As of January 2021, more than half of all genomic sequencing of COVID-19 was carried out in the UK.[187]

Origin of variantsEdit

See also: Antigenic escape and Escape mutation

Researchers have suggested that multiple mutations can arise in the course of the persistent infection of an immunocompromised patient, particularly when the virus develops escape mutations under the selection pressure of antibody or convalescent plasma treatment,[188][189] with the same deletions in surface antigens repeatedly recurring in different patients.[190]

Differential vaccine effectivenessEdit

See also: COVID-19 vaccine § Efficacy

Further information: 501.V2 variant § Vaccine evasion

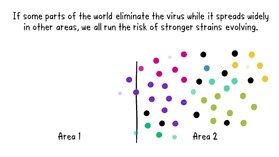

Play media

Play mediaWorld Health Organization video describing how variants proliferate in unvaccinated areas.

The potential emergence of a SARS-CoV-2 variant that is moderately or fully resistant to the antibody response elicited by the current generation of COVID-19 vaccines may necessitate modification of the vaccines.[191] Trials indicate many vaccines developed for the initial strain have lower efficacy for some variants against symptomatic COVID-19.[192] As of February 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration believed that all FDA authorized vaccines remained effective in protecting against circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.[191]

Early results suggest protection to the UK variant from the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines.[193][194]

One study indicated that the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine had an efficacy of 42–89% against the B.1.1.7 variant, versus 71–91% against non-B.1.1.7 variants.[195]

Preliminary data from a clinical trial indicates that the Novavax vaccine is ~96% effective for symptoms against the original variant and~86% against B.1.1.7.[196]

501.V2 variantEdit

Moderna has launched a trial of a vaccine to tackle the South African 501.V2 variant (also known as B.1.351).[197] On 17 February 2021, Pfizer announced neutralization activity was reduced by two-thirds for the 501.V2 variant, while stating that no claims about the efficacy of the vaccine in preventing illness for this variant could yet be made.[198] Decreased neutralizing activity of sera from patients vaccinated with the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines against B.1.351 was latter confirmed by several studies.[194][199] On 1 April 2021, an update on a Pfizer/BioNTech South African vaccine trial stated that the vaccine was 100% effective so far (i.e., vaccinated participants saw no cases), with six of nine infections in the placebo control group being the B.1.351 variant.[200]

In January 2021, Johnson & Johnson, which held trials for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in South Africa, reported the level of protection against moderate to severe COVID-19 infection was 72% in the United States and 57% in South Africa.[201]

On 6 February 2021, the Financial Times reported that provisional trial data from a study undertaken by South Africa's University of the Witwatersrand in conjunction with Oxford University demonstrated reduced efficacy of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine against the 501.V2 variant.[202] The study found that in a sample size of 2,000 the AZD1222 vaccine afforded only "minimal protection" in all but the most severe cases of COVID-19.[203] On 7 February 2021, the Minister for Health for South Africa suspended the planned deployment of about a million doses of the vaccine whilst they examine the data and await advice on how to proceed.[204][205]

In March 2021, it was reported that the "preliminary efficacy" of the Novavax vaccine (NVX-CoV2373) against B.1.351 for mild, moderate, or severe COVID-19[206] for HIV-negative participants is 51%.[207]

P1 variantEdit

The P1 variant (also known as 20J/501Y.V3), initially identified in Brazil, seems to partially escape vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.[199]

B.1.617 variantEditIn October 2020, a new double-mutation variant was discovered in India, which was named B.1.617. There were very few detections until January 2021 and by April it had spread to at least 20 countries in all continents except Antarctica and South America.[208][209][210] Among some 15 defining mutations, it has spike mutations D111D (synonymous), G142D,[211] P681R, E484Q[212] and L452R,[213] the latter two of which may cause it to easily avoid antibodies.[214] In an update on 15 April 2021, PHE designated B.1.617 as a 'Variant under investigation', VUI-21APR-01.[215]

See alsoEdit

RaTG13, the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2

Mòjiāng virus

Pandemic prevention § Surveillance and mapping

NotesEdit

^ a b In another source, GISAID name a set of 7 clades without the O clade but including a GV clade.[56]

^ According to the WHO, "Lineages or clades can be defined based on viruses that share a phylogenetically determined common ancestor".[57]

^ As of January 2021, at least one of the following criteria must be met in order to count as a clade in the Nextstrain system (quote from source):[52]

A clade reaches >20% global frequency for 2 or more months

A clade reaches >30% regional frequency for 2 or more months

A VOC (‘variant of concern’) is recognized (applies currently [6 January 2021] to 501Y.V1 and 501Y.V2)

ReferencesEdit

^ a b c d e Shahhosseini, Nariman; Babuadze, George; Wong, Gary; Kobinger, Gary (2021). "Mutation Signatures and In Silico Docking of Novel SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern". Microorganisms. 9 (5): 926. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9050926. PMID 33925854. S2CID 233460887. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

^ "Coronavirus variants and mutations: The science explained". BBC News. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ Kupferschmidt K (15 January 2021). "New coronavirus variants could cause more reinfections, require updated vaccines". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. doi:10.1126/science.abg6028. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ a b c d e f Zhukova A, Blassel L, Lemoine F, Morel M, Voznica J, Gascuel O (November 2020). "Origin, evolution and global spread of SARS-CoV-2". Comptes Rendus Biologies: 1–20. doi:10.5802/crbiol.29. PMID 33274614.

^ Official hCoV-19 Reference Sequence. www.gisaid.org. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

^ a b c Kumar, Sudhir; Tao, Qiqing; Weaver, Steven; Sanderford, Maxwell; Caraballo-Ortiz, Marcos A; Sharma, Sudip; Pond, Sergei L K; Miura, Sayaka. "An evolutionary portrait of the progenitor SARS-CoV-2 and its dominant offshoots in COVID-19 pandemic". Oxford Academic. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

^ "A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China" Fan Wu, Su Zhao, Bin Yu, Yan-Mei Chen, Wen Wang, Zhi-Gang Song, Yi Hu, Zhao-Wu Tao, Jun-Hua Tian, Yuan-Yuan Pei, Ming-Li Yuan, Yu-Ling Zhang, Fa-Hui Dai, Yi Liu, Qi-Min Wang, Jiao-Jiao Zheng, Lin Xu, Edward C Holmes, Yong-Zhen Zhang. PMID 32015508. PMC PMC7094943 doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3.

^ Comparative genomics reveals early emergence and biased spatio-temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Matteo Chiara, David S Horner, Carmela Gissi, Graziano Pesole PMID: 33605421 PMCID: PMC7928790 DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msab049

^ Zhengli, Shi; Team of 29 researchers at the WIV (3 February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. Bibcode:2020Natur.579..270Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMC 7095418. PMID 32015507.

^ Okada, Pilailuk; Buathong, Rome; Phuygun, Siripaporn; Thanadachakul, Thanutsapa; Parnmen, Sittiporn; Wongboot, Warawan; Waicharoen, Sunthareeya; Wacharapluesadee, Supaporn; Uttayamakul, Sumonmal; Vachiraphan, Apichart; Chittaganpitch, Malinee; Mekha, Nanthawan; Janejai, Noppavan; Iamsirithaworn, Sopon; Lee, Raphael TC; Maurer-Stroh, Sebastian (2020). "Early transmission patterns of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in travellers from Wuhan to Thailand, January 2020". Eurosurveillance. 25 (8). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.8.2000097.

^ Shahhosseini, Nariman; Wong, Gary; Kobinger, Gary; Chinikar, Sadegh (2021). "SARS-CoV-2 spillover transmission due to recombination event". Gene Reports. 23: 101045. doi:10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101045. PMC 7884226. PMID 33615041.

^ "The ancestor of SARS-CoV-2's Wuhan strain was circulating in late October 2019". News Medical. Retrieved 10 May 2020. Journal reference: Kumar, S. et al. (2021). An evolutionary portrait...

^ a b c d "Lineage descriptions". cov-lineages.org. Pango team.

^ a b c d e f g h i "SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions". cdc.org. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Variants: distribution of cases data". gov.uk. Government Digital Service.

^ "Global Report Investigating Novel Coronavirus Haplotypes". cov-lineages.org. Pango team.

^ a b c "Living Evidence – SARS-CoV-2 variants". Agency for Clinical Innovation. nsw.gov.au. Ministry of Health (New South Wales). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

^ "Nextstrain". nextstrain.org. Nextstrain.

^ a b c d e f g h i j "Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants". cdc.org (Science brief). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

^ a b c Chand et al. (2020), p. 6, Potential impact of spike variant N501Y.

^ Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, Barrett JC, Johnson R, Geidelberg L, et al. (4 January 2021). Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.12.30.20249034. hdl:10044/1/85239. Retrieved 22 March 2021 – via medRxiv.

^ Davies G, Jarvis C, Edmunds WJ, Jewell N, Diaz-Ordaz K, Keogh R (15 March 2021). "Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7". Nature (Published). 593 (7858): 270–274. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1. PMID 33723411. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

^ DChallen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read J, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L (10 March 2021). "Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study". The BMJ (Published). 372: n579. doi:10.1136/bmj.n579. PMC 7941603. PMID 33687922.

^ a b c d Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA – first update (Risk assessment). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2 February 2021.

^ a b "Lineage B.1.1.207". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 11 March 2021. Graphic shows B.1.1.207 detected in Peru, Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Costa Rica, South Korea, Canada, Australia, Japan, France, Italy, Ecuador, Mexico, UK and US.

^ a b c Sruthi S (10 February 2021). "Notable Variants And Mutation Of SARS-CoV-2". BioTecNika. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

^ "Lineage B.1.429". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 19 March2021. Graphic shows B.1.429 detected in the US, Mexico, Canada, UK, France, Denmark, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Guadeloupe, and Aruba.

^ "Southern California COVID-19 Strain Rapidly Expands Global Reach". Cedars-Sinai Newsroom. Los Angeles. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

^ Deng X, Garcia-Knight MA, Khalid MM, Servellita V, Wang C, Morris MK, et al. (March 2021). "Transmission, infectivity, and antibody neutralization of an emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant in California carrying a L452R spike protein mutation". MedRxiv (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2021.03.07.21252647. PMC 7987058. PMID 33758899.

^ Wadman M (23 February 2021). "California coronavirus strain may be more infectious – and lethal". Science News. doi:10.1126/science.abh2101. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

^ a b c d "SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – Denmark". WHODisease Outbreak News. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

^ a b c d Lassaunière R, Fonager J, Rasmussen M, Frische A, Strandh C, Rasmussen T, et al. (10 November 2020). SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations arising in Danish mink, their spread to humans and neutralization data(Preprint). Statens Serum Institut. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

^ Planas D, Bruel T, Grzelak L, et al. (14 April 2021). "Sensitivity of infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants to neutralizing antibodies". Nature Medicine. 27 (5): 917–924. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01318-5. PMID 33772244.

^ "Coronavirus: Sinovac vaccine gives 70 per cent less protection against South African variant, but Hongkongers urged to still get jab". www.scmp.com. 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

^ "PANGO lineages". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

^ a b "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus – Global subsampling (Filtered to B.1.617)". nextstrain.org. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

^ Nuki, Paul; Newey, Sarah (16 April 2021). "Arrival of India's 'double mutation' adds to variant woes, but threat posed remains unclear". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

^ Bhattacharya, Suryatapa (10 May 2021). "Coronavirus Strain Found in India Is a 'Variant of Concern,' WHO Says". The Wall Street Journal. Jason Douglas, Drew Hinshaw. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 11 May2021.

^ Yadav PD, Sapkal GN, Abraham P, Ella R, Deshpande G, Patil DY, et al. (April 2021). "Neutralization of variant under investigation B.1.617 with sera of BBV152 vaccinees". MedRxiv (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2021.04.23.441101. S2CID 233415846.

^ a b Kupferschmidt K (January 2021). "New mutations raise specter of 'immune escape'". Science. 371 (6527): 329–330. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..329K. doi:10.1126/science.371.6527.329. PMID 33479129.

^ "P.1". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

^ Coutinho RM, Marquitti FM, Ferreira LS, Borges ME, da Silva RL, Canton O, et al. (23 March 2021). "Model-based estimation of transmissibility and reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant". medRxiv (Preprint): 9. doi:10.1101/2021.03.03.21252706. S2CID 232119656. Retrieved 29 April 2021. The new variant was found to be about 2.6 times more transmissible (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 2.4–2.8) than previous circulating variant(s). ... Table 1: Summary of the fitted parameters and respective confidence intervals considering the entire period, November 1 2020-January 31, 2021 maintaining the same pathogenicity of the previous variant. Parameter: Relative transmission rate for the new variant. Estimate: 2.61. 2.5%: 2.45. 97.5%: 2.76.

^ a b c Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, Claro IM, Candido DD, Mishra S, et al. (April 2021). "Genomics and epidemiology of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil". Science (Preprint). doi:10.1126/science.abh2644. PMID 33853970. Within this plausible region of parameter space, P.1 can be between 1.7–2.4 (50% BCI, 2.0 median, with a 99% posterior probability of being >1) times more transmissible than local non-P1 lineages, and can evade 21–46% (50% BCI, 32% median, with a 95% posterior probability of being able to evade at least 10%) of protective immunity elicited by previous infection with non-P.1 lineages, corresponding to 54–79% (50% BCI, 68% median) cross-immunity

^ a b Roberts M (16 February 2021). "Another new coronavirus variant seen in the UK". BBC News. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

^ a b c "B.1.525". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 22 March2021.

^ a b c Public Health England (16 February 2021). "Variants: distribution of cases data". Gov.UK. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

^ Moustafa AM, Bianco C, Denu L, Ahmed A, Neide B, Everett J, et al. (21 April 2021). "Comparative Analysis of Emerging B.1.1.7+E484K SARS-CoV-2 isolates from Pennsylvania". bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.04.21.440801v1.

^ This table is an adaptation and expansion of Alm et al., figure 1.

^ a b Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O'Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, Ruis C, et al. (November 2020). "A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1403–1407. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. PMC 7610519. PMID 32669681. S2CID 220544096. Cited in Alm et al.

^ a b Alm E, Broberg EK, Connor T, Hodcroft EB, Komissarov AB, Maurer-Stroh S, et al. (The WHO European Region sequencing laboratories and GISAID EpiCoV group) (August 2020). "Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020". Euro Surveillance. 25 (32). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001410. PMC 7427299. PMID 32794443.

^ a b "Nextclade" (What are the clades?). clades.nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January2021.

^ a b c d Bedford T, Hodcroft B, Neher RA (6 January 2021). "Updated Nextstrain SARS-CoV-2 clade naming strategy". nextstrain.org/blog. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

^ a b c d Zhang W, Davis B, Chen SS, Martinez JS, Plummer JT, Vail E (2021). "Emergence of a novel SARS-CoV-2 strain in Southern California, USA". MedRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.01.18.21249786. S2CID 231646931.

^ "PANGO lineages-Lineage B.1.1.28". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 4 February 2021.[failed verification]

^ "Variant: 20J/501Y.V3". covariants.org. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April2021.

^ "clade tree (from 'Clade and lineage nomenclature')". www.gisaid.org. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

^ a b c d WHO Headquarters (8 January 2021). "3.6 Considerations for virus naming and nomenclature". SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequencing for public health goals: Interim guidance, 8 January 2021. World Health Organization. p. 6. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ "Don't call it the 'British variant.' Use the correct name: B.1.1.7". STAT. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

^ Flanagan R (2 February 2021). "Why the WHO won't call it the 'U.K. variant', and you shouldn't either". Coronavirus. Retrieved 12 February2021.

^ For a list of sources using names referring to the country in which the variants were first identified, see, for example, Talk:South African COVID variant and Talk:U.K. Coronavirus variant.

^ World Health Organization (15 January 2021). "Statement on the sixth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". Retrieved 18 January 2021.

^ Koyama T, Platt D, Parida L (July 2020). "Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 98 (7): 495–504. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.253591. PMC 7375210. PMID 32742035. We detected in total 65776 variants with 5775 distinct variants.

^ "Global phylogeny, updated by Nextstrain". GISAID. 18 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

^ Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. (December 2018). Kelso J (ed.). "Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution". Bioinformatics. 34 (23): 4121–4123. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407. PMC 6247931. PMID 29790939.

^ "cov-lineages/pangolin: Software package for assigning SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences to global lineages". Github. Retrieved 2 January2021.

^ Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O'Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, Ruis C, et al. (March 2021). "Addendum: A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology". Nature Microbiology. 6(3): 415. doi:10.1038/s41564-021-00872-5. PMC 7845574. PMID 33514928.

^ IDSA Contributor (2 February 2021). "COVID "Mega-variant" and eight criteria for a template to assess all variants". Science Speaks: Global ID News. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

^ Griffiths E, Tanner J, Knox N, Hsiao W, Van Domselaar G (15 January 2021). "CanCOGeN Interim Recommendations for Naming, Identifying,and Reporting SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern" (PDF). CanCOGeN (nccid.ca). Retrieved 25 February 2021.

^ "Detection of new SARS-CoV-2 variants related to mink" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

^ Danish Covid mink variant 'very likely extinct', but controversial cull continues

^ Larsen HD, Fonager J, Lomholt FK, Dalby T, Benedetti G, Kristensen B, et al. (February 2021). "Preliminary report of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in mink and mink farmers associated with community spread, Denmark, June to November 2020". Euro Surveillance. 26 (5). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.5.210009. PMC 7863232. PMID 33541485.

^ "Covid: Ireland, Italy, Belgium and Netherlands ban flights from UK". BBC News. 20 December 2020.

^ Chand M, Hopkins S, Dabrera G, Achison C, Barclay W, Ferguson N, et al. (21 December 2020). Investigation of novel SARS-COV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01 (PDF) (Report). Public Health England. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

^ "PHE investigating a novel strain of COVID-19". Public Health England (PHE). 14 December 2020.

^ Rambaut A, Loman N, Pybus O, Barclay W, Barrett J, Carabelli A, et al. (2020). Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations (Report). Written on behalf of COVID-19 Genomics Consortium UK. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

^ Kupferschmidt K (20 December 2020). "Mutant coronavirus in the United Kingdom sets off alarms but its importance remains unclear". Science Mag. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

^ "New evidence on VUI-202012/01 and review of the public health risk assessment". khub.net. 15 December 2020.

^ "COG-UK Showcase Event". Retrieved 25 December 2020 – via YouTube.

^ "New evidence on VUI-202012/01 and review of the public health risk assessment". Retrieved 4 January 2021.

^ "Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England". CMMID Repository. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via GitHub.

Cited in European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (21 January 2021). "Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA – first update" (PDF). Stockholm: ECDC. p. 9. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

^ Gallagher J (22 January 2021). "Coronavirus: UK variant 'may be more deadly'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

^ Peter Horby; Catherine Huntley; Nick Davies; John Edmunds; Neil Ferguson; Graham Medley; Andrew Hayward; Muge Cevik; Calum Semple (11 February 2021). "NERVTAG paper on COVID-19 variant of concern B.1.1.7: NERVTAG update note on B.1.1.7 severity (2021-02-11)" (PDF). www.gov.uk.

^ Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study, Dan Frampton, et al., The Lancet, Online, April 12, 2021

^ PANGO lineages Lineage B.1.1.7 cov-lineages.org, accessed 15 May 2021

^ Mandavilli A (5 March 2021). "In Oregon, Scientists Find a Virus Variant With a Worrying Mutation – In a single sample, geneticists discovered a version of the coronavirus first identified in Britain with a mutation originally reported in South Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

^ Chen RE, Zhang X, Case JB, Winkler ES, Liu Y, VanBlargan LA, et al. (March 2021). "Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies". Nature Medicine. 27 (4): 717–726. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. PMC 8058618. PMID 33664494.

^ "B.1.1.7 Lineage with S:E484K Report". outbreak.info. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

^ a b "Detection of SARS-CoV-2 P681H Spike Protein Variant in Nigeria". Virological. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

^ "Queensland travellers have hotel quarantine extended after Russian variant of coronavirus detected". www.abc.net.au. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

^ "Latest update: New Variant Under Investigation designated in the UK". www.gov.uk. 4 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

^ a b c d "South Africa announces a new coronavirus variant". The New York Times. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

^ a b Wroughton L, Bearak M (18 December 2020). "South Africa coronavirus: Second wave fueled by new strain, teen 'rage festivals'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

^ Mkhize Z (18 December 2020). "Update on Covid-19 (18th December 2020)" (Press release). South Africa. COVID-19 South African Online Portal. Retrieved 23 December 2020. Our clinicians have also warned us that things have changed and that younger, previously healthy people are now becoming very sick.

^ Abdool Karim, Salim S. (19 December 2020). "The 2nd Covid-19 wave in South Africa:Transmissibility & a 501.V2 variant, 11th slide". www.scribd.com.

^ Lowe D (22 December 2020). "The New Mutations". In the Pipeline. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 23 December 2020. I should note here that there's another strain in South Africa that is bringing on similar concerns. This one has eight mutations in the Spike protein, with three of them (K417N, E484K and N501Y) that may have some functional role.

^ "Statement of the WHO Working Group on COVID-19 Animal Models (WHO-COM) about the UK and South African SARS-CoV-2 new variants"(PDF). World Health Organization. 22 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

^ "Novel mutation combination in spike receptor binding site" (Press release). GISAID. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

^ a b c "New California Variant May Be Driving Virus Surge There, Study Suggests". New York Times. 19 January 2021.

^ "SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 24 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

^ Shen X, Tang H, Pajon R, Smith G, Glenn GM, Shi W, et al. (April 2021). "Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Variants B.1.429 and B.1.351". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2103740. PMC 8063884. PMID 33826819.

^ "Local COVID-19 Strain Found in Over One-Third of Los Angeles Patients". news wise (Press release). California: Cedars Sinai Medical Center. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

^ a b "B.1.429". Rambaut Group, University of Edinburgh. PANGO Lineages. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

^ a b "B.1.429 Lineage Report". Scripps Research. outbreak.info. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

^ "COVID-19 Variant First Found in Other Countries and States Now Seen More Frequently in California". www.cdph.ca.gov. Retrieved 30 January2021.

^ Weise E, Weintraub K. "New strains of COVID swiftly moving through the US need careful watch, scientists say". USA Today. Retrieved 30 January2021.

^ a b Zimmer, Carl; Mandavilli, Apoorva (14 May 2021). "How the United States Beat the Variants, for Now". New York Times. Retrieved 17 May2021.

^ "Delta-PCR-testen" [The Delta PCR Test] (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

^ a b "GISAID hCOV19 Variants (see menu option 'G/484K.V3 (B.1.525)')". www.gisaid.org. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

^ a b "Status for udvikling af SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) i Danmark" [Status of development of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) in Denmark] (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 27 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

^ "Varianten van het coronavirus SARS-CoV-2" [Variants of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2] (in Dutch). Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM. 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

^ "A coronavirus variant with a mutation that 'likely helps it escape' antibodies is already in at least 11 countries, including the US". Business Insider. 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

^ "En ny variant av koronaviruset er oppdaget i Norge. Hva vet vi om den?" [A new variant of the coronavirus has been discovered in Norway. What do we know about it?] (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

^ Cullen P (25 February 2021). "Coronavirus: Variant discovered in UK and Nigeria found in State for first time". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 February 2021. Gataveckaite G (25 February 2021). "First Irish case of B1525 strain of Covid-19 confirmed as R number increases". Irish Independent. Retrieved 25 February 2021. McGlynn M (25 February 2021). "Nphet confirm new variant B1525 detected in Ireland as 35 deaths and 613 cases confirmed". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

^ Mandavilli A (24 February 2021). "A New Coronavirus Variant Is Spreading in New York, Researchers Report". The New York Times.

^ "PANGO lineages". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

^ a b c d Koshy J (8 April 2021). "Coronavirus | Indian 'double mutant' strain named B.1.617". The Hindu.

^ "India's variant-fuelled second wave coincided with spike in infected flights landing in Canada". Toronto Sun. 10 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

^ "Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 11 May 2021". World Health Organization. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

^ Cherian, Sarah; Potdar, Varsha; Jadhav, Santosh; Yadav, Pragya; Gupta, Nivedita; Das, Mousmi; Rakshit, Partha; Singh, Sujeet; Abraham, Priya; Panda, Samiran (24 April 2021). ""Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations, L452R, E484Q and P681R, in the second wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India"". doi:10.1101/2021.04.22.440932. S2CID 233415787. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

^ Shrutirupa (17 April 2021). "Is This COVID–20? | Double Mutant Strain Explained". Self Immune. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

^ "'Double mutant': What are the risks of India's new Covid-19 variant". www.bbc.co.uk/news. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

^ Haseltine WA. An Indian SARS-CoV-2 Variant Lands In California. More Danger Ahead? Forbes.com, Apr 12, 2021, accessed 14 April 2021

^ "Confirmed cases of COVID-19 variants identified in UK (see: Thursday 15 April/New Variant Under Investigation (VUI) designated)". www.gov.uk. 15 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

^ "Confirmed cases of COVID-19 variants identified in UK (see: Two VUIs added to B.1.617 group)". www.gov.uk. 29 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May2021.

^ "British scientists warn over Indian coronavirus variant". Reuters. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

^ "SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 6 May 2021". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

^ New coronavirus variant found in West Bengal www.thehindu.com, accessed 23 April 2021

^ What is the new 'triple mutant variant' of Covid-19 virus found in Bengal? How bad is it? www.indiatoday.in, accessed 23 April 2021

^ PANGO lineages Lineage B.1.618 cov-lineages.org, accessed 23 April 2021

^ Unidentified coronavirus strain found in eastern Lithuania 20 April 2021 www.lrt.lt accessed 6 May 2021

^ "Japan finds new coronavirus variant in travelers from Brazil". Japan Today. Japan. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

^ a b c d e f Faria NR, Claro IM, Candido D, Moyses Franco LA, Andrade PS, Coletti TM, et al. (12 January 2021). "Genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus: preliminary findings". CADDE Genomic Network. virological.org. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

^ Covid-19 Genomics UK Consortium (15 January 2021). "COG-UK Report on SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations of interest in the UK" (PDF). www.cogconsortium.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

^ "P.1 report". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

^ a b c Voloch CM, da Silva Francisco R, de Almeida LG, Cardoso CC, Brustolini OJ, Gerber AL, et al. (Covid19-UFRJ Workgroup) (2020). "Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil". doi:10.1101/2020.12.23.20248598. S2CID 229379623 – via MedRxiv.

^ "PANGO lineages Lineage P.2". COV lineages. Retrieved 28 January2021. P.2… Alias of B.1.1.28.2, Brazilian lineage

^ Nascimento V, Souza V (25 February 2021). "COVID-19 epidemic in the Brazilian state of Amazonas was driven by long-term persistence of endemic SARS-CoV-2 lineages and the recent emergence of the new Variant of Concern P.1". Research Square. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-275494/v1. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

^ Andreoni M, Londoño E, Casado L (3 March 2021). "Brazil's Covid Crisis Is a Warning to the Whole World, Scientists Say – Brazil is seeing a record number of deaths, and the spread of a more contagious coronavirus variant that may cause reinfection". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

^ Zimmer C (1 March 2021). "Virus Variant in Brazil Infected Many Who Had Already Recovered From Covid-19 – The first detailed studies of the so-called P.1 variant show how it devastated a Brazilian city. Now scientists want to know what it will do elsewhere". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

^ Garcia-Beltran W, Lam E, Denis K (12 March 2021). "Circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity". doi:10.1101/2021.02.14.21251704. Retrieved 14 April2021 – via medrxiv.

^ Sofia Moutinho (4 May 2021). "Chinese COVID-19 vaccine maintains protection in variant-plagued Brazil".

^ Gaier R (5 March 2021). "Exclusive: Oxford study indicates AstraZeneca effective against Brazil variant, source says". Reuters. Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

^ "Exclusive: Oxford study indicates AstraZeneca effective against Brazil variant, source says". Reuters. Rio de Janeiro. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

^ Simões E, Gaier R (8 March 2021). "CoronaVac e Oxford são eficazes contra variante de Manaus, dizem laboratórios" [CoronaVac and Oxford are effective against Manaus variant, say laboratories]. UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). Reuters Brazil. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

^ "DOH confirms detection of 2 SARS-CoV-2 mutations in Region 7". ABS-CBN News. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

^ Santos E (13 March 2021). "DOH reports COVID-19 variant 'unique' to PH, first case of Brazil variant". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 17 March2021.

^ "DOH confirms new COVID-19 variant first detected in PH, first case of Brazil variant". ABS-CBN News. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March2021.

^ "PH discovered new COVID-19 variant earlier than Japan, expert clarifies". CNN Philippines. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

^ "Japan detects new coronavirus variant from traveler coming from PH". CNN Philippines. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

^ "UK reports 2 cases of COVID-19 variant first detected in Philippines". ABS-CBN. 17 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

^ "Covid-19: Sarawak detects variant reported in the Philippines". 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

^ Tandel, Dixit; Gupta, Divya; Sah, Vishal; Harshan, Krishnan Harinivas (30 April 2021). "N440K variant of SARS-CoV-2 has Higher Infectious Fitness". bioRxiv: 2021.04.30.441434. doi:10.1101/2021.04.30.441434.

^ Bhattacharjee, Sumit (3 May 2021). "COVID-19 | A.P. strain at least 15 times more virulent". The Hindu.

^ "Hyderabad: Mutant N440K 10 times more infectious than parent strain".

^ a b c d Greenwood M (15 January 2021). ""What Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 are Causing Concern?"]". News Medical Lifesciences. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

^ "University of Graz". www.uni-graz.at. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

^ "Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly known as Wuhan coronavirus and 2019-nCoV) – what we can find out on a structural bioinformatics level". Innophore. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

^ Singh A, Steinkellner G, Köchl K, Gruber K, Gruber CC (February 2021). "Serine 477 plays a crucial role in the interaction of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with the human receptor ACE2". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 4320. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.4320S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83761-5. PMC 7900180. PMID 33619331.

^ "BioNTech: We aspire to individualize cancer medicine". BioNTech. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

^ Schroers B, Gudimella R, Bukur T, Roesler T, Loewer M, Sahin U (4 February 2021). "Large-scale analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike-glycoprotein mutants demonstrates the need for continuous screening of virus isolates". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.02.04.429765. S2CID 231885609.

^ a b c Mandavilli A, Mueller B (2 March 2021). "Why Virus Variants Have Such Weird Names". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

^ "escape mutation". HIV i-Base. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

^ Wise J (February 2021). "Covid-19: The E484K mutation and the risks it poses". BMJ. 372: n359. doi:10.1136/bmj.n359. PMID 33547053. S2CID 231821685.

^ a b c "Brief report: New Variant Strain of SARS-CoV-2 Identified in Travelers from Brazil" (PDF) (Press release). Japan: NIID (National Institute of Infectious Diseases). 12 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January2021.

^ "Technical briefing 5" (PDF). Gov.uk. Public Health England. p. 17. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ Greaney A (4 January 2021). "Comprehensive mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human serum antibodies". bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.12.31.425021.

^ Rettner R (2 February 2021). "UK coronavirus variant develops vaccine-evading mutation – In a handful of instances, the U.K. coronavirus variant has developed a mutation called E484K, which may impact vaccine effectiveness". Live Science. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ Achenbach J, Booth W (2 February 2021). "Worrisome coronavirus mutation seen in U.K. variant and in some U.S. samples". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

^ "People Are Talking About A 'Double Mutant' Variant In India. What Does That Mean?". NPR.org. Retrieved 27 April 2021. ...scientifically, the term "double mutant" makes no sense, Andersen says. "SARS-CoV-2 mutates all the time. So there are many double mutants all over the place. The variant in India really shouldn't be called that."

^ a b COG-UK update on SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations of special interest: Report 1 (PDF) (Report). COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium (COG-UK). 20 December 2020. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

^ "Researchers Discover New Variant of COVID-19 Virus in Columbus, Ohio". wexnermedical.osu.edu. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January2021.

^ Tu H, Avenarius MR, Kubatko L, Hunt M, Pan X, Ru P, et al. (26 January 2021). "Distinct Patterns of Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variants including N501Y in Clinical Samples in Columbus Ohio". bioRxiv: 2021.01.12.426407. doi:10.1101/2021.01.12.426407. S2CID 231666860.

^ a b c Maison DP, Ching LL, Shikuma CM, Nerurkar VR (January 2021). "Genetic Characteristics and Phylogeny of 969-bp S Gene Sequence of SARS-CoV-2 from Hawaii Reveals the Worldwide Emerging P681H Mutation". bioRxiv: 2021.01.06.425497. doi:10.1101/2021.01.06.425497. PMC 7805472. PMID 33442699.

^ Schraer R (18 July 2020). "Coronavirus: Are mutations making it more infectious?". BBC News. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

^ "New, more infectious strain of COVID-19 now dominates global cases of virus: study". medicalxpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

^ Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. (August 2020). "Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus". Cell. 182 (4): 812–827.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. PMC 7332439. PMID 32697968.

^ Hou YJ, Chiba S, Halfmann P, Ehre C, Kuroda M, Dinnon KH, et al. (December 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo". Science. 370 (6523): 1464–1468. Bibcode:2020Sci...370.1464H. doi:10.1126/science.abe8499. PMC 7775736. PMID 33184236. an emergent Asp614→Gly (D614G) substitution in the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 strains that is now the most prevalent form globally

^ Butowt R, Bilinska K, Von Bartheld CS (October 2020). "Chemosensory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Integration of Genetic and Epidemiological Data Points to D614G Spike Protein Variant as a Contributing Factor". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 11 (20): 3180–3184. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00596. PMC 7581292. PMID 32997488.

^ "Study shows P681H mutation is becoming globally prevalent among SARS-CoV-2 sequences". News-Medical.net. 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

^ "Malaysia identifies new Covid-19 strain, similar to one found in 3 other countries". The Straits Times. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 10 January2021. Tan Sri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah, said it is still unknown whether the strain - dubbed the "A701B" mutation - is more infectious than usual

^ "Duterte says Sulu seeking help after new COVID-19 variant detected in nearby Sabah, Malaysia". GMA News. 27 December 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

^ a b c "The current situation and Information on the Spike protein mutation of Covid-19 in Malaysia". Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia/ covid-19 Malaysia/ covid-19.moh.gov.my. 25 December 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

^ a b c COVID-19 A701V mutation spreads to third wave clusters 25 December 2020 focusmalaysia.my, accessed 13 May 2021

^ a b The current situation and Information on the Spike protein mutation of Covid-19 in Malaysia 25 December 2020 covid-19.moh.gov.my, accessed 13 May 2021

^ Variants of Concerns (VOC), B.1.524, B.1.525, South African B.1.351, STRAIN D614G, A701V, B1.1.7 14 April 2021, covid-19.moh.gov.my, accessed 15 May 2021